The German writer Irmgard Keun lived a fascinating life. Having enjoyed great success with her first two novels Gilgi, One of Us (1931) and The Artificial Silk Girl (both of which I adored), she found herself blacklisted when the Nazis swept to power in 1933. By 1936, Keun was travelling around Europe in the company of her lover, the Jewish writer Joseph Roth. After Midnight (1937) and Child of All Nations (1938) were written while Keun was in exile abroad, with the writer finally returning to Germany in 1940 under an assumed name – possibly helped by a false newspaper report of her suicide. A final novel, Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart, was published in Germany in 1950 but has only recently been translated into English by Michael Hofmann in 2021.

Ferdinand differs from Keun’s earlier novels by virtue of its focus on a male character. So while Gilgi, Silk Girl and Midnight, all feature strong women, full of determination and life, Ferdinand is narrated by a dandyish daydreamer with a tendency to drift. Consequently, Ferdinand seems to lack the narrative drive of Keun’s previous work, which makes for a somewhat frustrating read (for this reader at least). Nevertheless, there are still various elements to enjoy here, although it’s probably best suited to die-hard Keun fans rather than first-time readers of her work.

Set in post-war Cologne, where black-market trading and other dodgy activities are rife, the novel reads like a series of pen portraits and sketches as our eponymous hero, Ferdinand Timpe, tries to make his way in a rapidly changing world. Just like Ferdinand himself, the narrative meanders around, bumping into various acquaintances and members of the extended Timpe family, each one more eccentric and absurd than the last. Take Ferdinand’s brother Luitpold as an example, a furniture maker in southern Germany – a man who always manages to stay afloat, despite his dire money management.

Luitpold represents the type of good fellow who in nineteenth-century novels gets into trouble by issuing bonds for unreliable friends, allowing bills to fall due, paying allowances to children who were not his, and opening his heart and his wallet to impoverished widows. By the rules of our rough new world he is classified as a noble idiot. (p. 105)

Ferdinand’s future mother-in-law is another strange one, eagerly combing the bombed-out city for all manner of booty from typewriters to louche paintings.

The city seemed wiped out, destroyed. But some things weren’t. In the midst of the ruins there were a few intact, abandoned houses and flats in pallid, ghostly glory. Everything belonged to everyone. Insatiable and obsessed, my forget-me-not-blue mother-in-law went on the prowl, and snaffled among other things as sewing machine, various typewriters, four rugs, seventeen eggcups, a gilt frame, a bombproof door, a poultry cage, and a pompous drawing-room painting depicting a voluptuous woman lying prone in pink, puffy nudity, a blue moth teetering on the end of her pink index finger, and the whole thing somehow casual. (p. 60)

Funnily enough, the stolen painting gives rise to a particularly amusing anecdote when the former owners of the artwork appear on the scene. But despite this troublesome development, Ferdinand’s mother-in-law, Frau Klatte, insists that the painting is a treasured heirloom, passed down through her family from one generation to the next. As far as Frau Klatte sees it, the former owners are ‘awful people’ who are ‘not even properly married’, and a protracted tussle over the item subsequently ensues.

At heart, Ferdinand lacks ambition, which contributes to his rather aimless approach to life. As such, he recognises his lack of suitability for various professions, ranging from teaching and academia to administration and business. In a case of mistaken identity, Ferdinand lands a gig as a writer for Red Dawn, an emerging literary journal, but he struggles to settle on a subject for his story. Eventually though, another job turns up, with Ferdinand acting as a kind of agony aunt for unhappy wives looking to let off steam about their husbands’ shortcomings.

Most women would rather be married unhappily than not at all. Besides they are rarely as unhappy as they think they are. Some have an inborn martyr complex and take suffering for a sign of moral superiority. They like to be pitied. For these wives I have a pained frown in the corner of my mouth and a look of melancholy sympathy. That sees me through, and I don’t even need to speak. (p. 117)

As Ferdinand makes his way through the city, he is also on the lookout for a new suitor for his fiancée, Luise. Having allowed himself to become engaged to Luise before the war, Ferdinand now wishes to extricate himself from the arrangement. In truth, after a stint as a prisoner of war, he really wants to live alone for a while as he adjusts to a world of freedom. The trouble is, there are Luise’s feelings to be considered, hence our protagonist’s quandary on what to do for the best. As the novel draws to a close, an ironic development comes to Ferdinand’s rescue, but I’ll let you discover that for yourself should you decide to read the book.

The novel ends with a party at Cousin Johanna’s place, a reunion of sorts as various friends, relatives and strangers come together, fuelled by an assortment of music and drink. It’s a fitting end to a somewhat disjointed novel – but maybe that’s a perfectly accurate reflection of life in post-war Cologne, shortly after Germany’s currency reform in 1948.

So, in summary then, not an entirely satisfying experience for me, although Keun’s pithy observations on human nature and various aspects of 20th century life are always interesting to read. For other (more positive) views on this book, Grant’s review and Max’s summary are worth reading, accessible via the links.

Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart is published by Penguin Books; personal copy. (Read for Lizzy’s German Lit Month and Novellas in November.)

An especially interesting review, Jacqui, I really learned from it and my curiosity is on the rise about this author. Cheers!

Thanks, Jennifer. Glad you found it interesting. :)

Not an author I’ve read so far, but your review makes me interested to explore her work; but as you say, perhaps one of the others first.

Yes, definitely. Either The Artificial Silk Girl or Gilgi would be the best place to start to get a good feel for her style. She’s an excellent writer and well worth exploring, especially if you’re interested in Weimar-era Germany.

Reblogged this on penwithlit and commented:

I really like Keun and intrigued by her relationship with Joseph Roth. Hoffman is a brilliant translator too. Currently reading Käsebier conquers the Kurfürstendamm

Novel by Gabriele Tergit

Thanks for sharing my review, much appreciated! Yes, I’m intrigued by her relationship with Roth, too. There’s a new Roth biography by Kieron Pim – Endless Flight, I think it’s called. I’ve seen a couple of people recommending it on social media, and it seems to be picking up some excellent reviews. I must take a look at it at some point to see how much it goes into his relationship with Keun…

I loved After Midnight and especially want to read Child of All Nations, and am curious about this one. It sounds interesting on its own terms with its portrayal of the post-war setting and uncertainties.

Child of All Nations is the only Keun I have let to read, so I’ll be interested to hear what you think of it!

Interesting review, Jacqui, and although I’ve read and loved several of Keun’s books, I’d not come across this one (probably because it’s only just been translated!) It definitely sounds to have a very different focus to the other books, and I wonder if it’s, as you say, reflective of post-War Germany. I shall give it a go at some point, but with your thoughts in mind!

Yes, it feels like the weakest of her books, so maybe not surprising that it’s only just been translated. That said, there are some terrific little pen portraits of various characters here, all of whom feel authentic (as if they were based on real life figures or observations), so it’s not without merit. You might get more out of it than I did, so I’ll be fascinated to see!

Lovely review as always. Love the description of that painting of the woman ‘lying prone in pink, puffy, nudity.’ When I come across a book by Irmgard Keun I will snap it up.

Thanks, Gert. Yes, she’s a terrific writer with a gimlet eye for detail and a sharp observation. All her others have been great, and I’d have no hesitations whatsoever in recommending them. So yes, if you happen to see any of her books (with the possible exception of this one), do snap them up!

Interesting review Jacqui, this sounds a little unfocused? Keun does sound like an interesting writer though.

Yes, she writes brilliantly about spirited young women trying to navigate the complexities of life in pre-war Germany. I’d recommend either The Artificial Silk Girl or Gilgi, One of Us as an excellent place to begin.

Pingback: It’s Novellas in November time – add your links here! #NovNov22

Despite your mixed feelings about the book, you certainly made me interested in it. Until your review, I had never heard of the author or her books. As I read your description of the novel, it seemed to me that Keun was presenting a snapshot of a time that was extremely complicated.

Yes, it must have been a strange time, full of uncertainties and shifting dynamics. The currency reform happened in 1948, and it’s referred to in the novel as a backdrop to story. Nevertheless, she’s a fascinating writer and well worth considering, especially if you’re interested in exploring pre-WW2 Germany from a female perspective – Gilgi, Silk Girl and After Midnight are all terrific.

Her books are now on my TBR list, which grows longer by the minute. ;)

Ha! Yes, I know that feeling… :-)

Thanks for the link. Like you I found it an interesting contrast to her pre-war books – in the end I felt it was as interesting a portrait of post-war Germany as they were of the 1930s, the changed tone perhaps a symptom of the changed times.

Yes, I think you’re right about the nature of the novel being a reflection of the uncertainties and shifting dynamics of post-war Germany. It must have been a strange environment to navigate…and I’m probably being a little unfair in expecting the novel to be another Gilgi or Silk Girl given the setting!

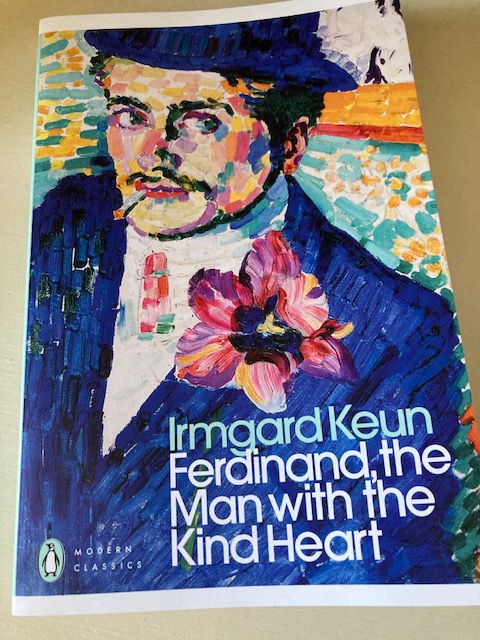

Having really enjoyed The Artificial Silk Girl, Child of All Nations and After Midnight, I am embarrassed to admit I hadn’t even heard of this one. I absolutely love the cover image. So it’s a shame you found this quite a frustrating read. I wonder how I would get on with it, I shall keep it in mind though as I really enjoyed those quotes you provide.

Yes, the cover is fabulous, isn’t it? So eye-catching. And the writing is great, just as we’ve come to expect from Keun. There are nuggets of gold in here for sure, but the overall novel just fell a bit short of the sum of its parts for me. I’ll be interested to hear your take should you decide to read it!

Pingback: A-Z Index of Book Reviews (listed by author) | JacquiWine's Journal

I’ve read two of Keun’s novels (After Midnight & Child of All Nations), both of which I really enjoyed; I hope eventually to read them all. After your review, however, Ferdinand goes to the bottom of the list!

Haha! Yes, I’d put Gilgi and The Artificial Silk Girl well ahead of Ferdinand in the Keun pecking order, especially as they’re closer in style to After Midnight!

I’ve not read Keun at all but your enthusiastic reviews have definitely put her on my list. This does sound fascinating even if it wasn’t totally satisfying.

Yes, it was interesting to read this one, but I’m glad it wasn’t my first experience of Keun!

Her early novels are fantastic – I think she’s at her best when writing from the female perspective, especially young, spirited women trying to navigate the complexities of life in 1930s Germany.

Pingback: German Literature Month XII Author Index – Lizzy’s Literary Life (Volume 2)

I found this review stored in my tabs. We discussed this I think. Looking here I think you capture it well. I liked it, but I agree it’s her weakest. Still enjoyable, for me anyway, but if it had been my first by her I might not have gone on to read the rest. Perhaps one for completists as you say, but then I am a Keun completist!

Thanks, Max. Yes, I definitely prefer the novellas featuring young women. That’s where she’s strongest, I think, portraying spirited creatures like Doris (from Silk Girl) and Gilgi (from her debut). I still need to pick up Child of All Nations, which I think you may have read?

I have. I’d put it above these but below say ASG or Gilgi. I agree she’s at her best with her portraits of spirited young women. Worth reading though.

Great. It’s on the list, so I’m sure I’ll get to it at some point!