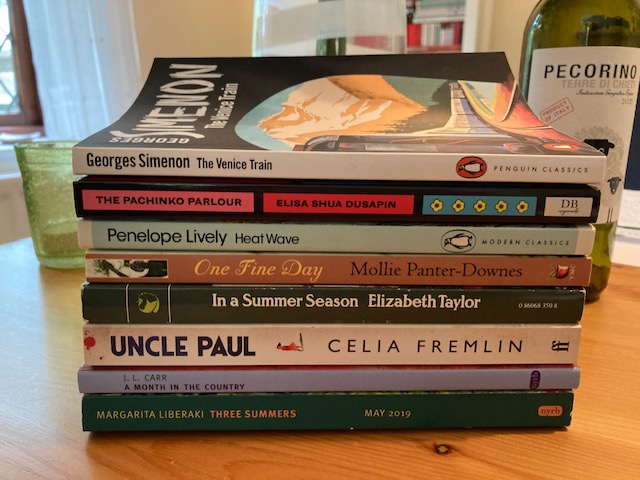

Back in early July, when I posted a piece on some of my favourite summer reads, it soon became clear from your comments that there would be more than enough potential for another round-up of recommendations. So, here I am with part two of my favourite summer books, featuring illicit affairs, heady coming-of-age stories and nightmare summer holidays steeped in fear and paranoia. There’s something for virtually every reader here. (As usual, I’ve summarised each book, but you can read my reviews in full by clicking on the relevant links.)

One Fine Day by Mollie Panter-Downes

In this beautifully written novel, we follow a day in the life of the Marshalls, an upper-middle-class family struggling to find a new way to live in an England altered irrevocably by WW2. Set on a blisteringly hot day in the summer of 1946, the novel captures a moment of great social change as thousands of families find themselves having to adapt to significant shifts in circumstances. For some inhabitants of Wealding, a picturesque village in the home counties, the war has opened up fresh opportunities and pastures new; but for others like Laura Marshall and her husband Stephen, it has led to a marked decline in living standards compared to the glory days of the late 1930s. Several threads and encounters come together to form a vivid picture of a nation trying to come to terms with new ways of life and the accompanying changes to its social fabric. A little like a cross between Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway and an Elizabeth Taylor novel, this was a wonderful discovery for me back in 2017.

A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr

A sublime, deeply affecting book about love, loss and the restorative power of art. Set in small Yorkshire village in the heady summer of 1920, Carr’s novella is narrated by Tom Birkin, a young man still dealing with the effects of shell shock following the traumas of WW1. A Southerner by nature, Birkin has come to Oxgodby to restore a Medieval wall painting in the local church – much to the annoyance of the vicar, Reverend Keach, who resents the restorer’s presence in his domain. However, there is another purpose to Birkin’s visit: to find an escape or haven of sorts, an immersive distraction from the emotional scars of the past. Above all, this is an elegant novella imbued with a strong sense of longing, a nostalgia for an idyllic world. It also perfectly captures the ephemeral nature of time – the idea that our lives can turn on the tiniest of moments, the most fleeting of chances to be grasped before they are lost forever. A masterpiece in miniature, full of yearning and desire.

Three Summers by Margarita Liberaki (tr. Karen Van Dyck)

First published in 1946, Three Summers is something of a classic of Greek literature, a languid coming-of-age novel featuring three sisters set over three consecutive summer seasons. At first sight, it might appear that the book presents a simple story, one of three very different young women growing up in the idyllic Greek countryside. However, there are darker, more complex issues bubbling away under the surface as the sisters must learn to navigate the choices that will shape the future directions of their lives. Sexual awakening is a major theme, with the novel’s lush and sensual tone echoing the rhythms of the natural world. Ultimately though, it is the portrait of the three sisters that really shines through – the opportunities open to them and the limitations society may wish to dictate. This a novel about working out who you are as a person and finding your place in the world; of being aware of the consequences of certain life choices and everything these decisions entail.

Heat Wave by Penelope Lively

If you like Tessa Hadley’s fiction (especially her excellent novel, The Past), chances are this book will also suit you. Fifty-five-year-old Pauline – a freelance editor – is spending the summer at World’s End, her cottage in the English countryside. Residing in the adjacent cottage are Pauline’s daughter, Teresa, Teresa’s husband, Maurice, and their baby, Luke. Ostensibly, the family is there to enable Maurice – a writer of some promise – to complete his book on the history of tourism. What follows is a character-driven story of jealousy, betrayal and frustration, all unfolding over a dry, claustrophobic summer underscored by a growing sense of pressure. Lively’s descriptions of the natural world are so evocative, clearly reflecting the novel’s simmering tension through images of the scorched landscape withering in the blistering heat.

In a Summer Season by Elizabeth Taylor

An excellent novel about love, family tensions and the fragile nature of changing relationships, all conveyed in Taylor’s precise, insightful style. The story revolves around Kate Heron, previously widowed and now married to Dermot, ten years her junior. Also living with the Herons are Kate’s children from her first marriage: twenty-two-year-old Tom, struggling to please his punctilious grandfather in the family business, and sixteen-year-old Louisa, a slightly awkward teenager home from boarding school for the holidays. Completing the immediate family are Kate’s elderly aunt, Ethel, a kindly, sharp-eyed woman who delights in noting the smallest of developments in the Herons’ marital relationship, and the cook, Mrs Meacock, who longs to travel and compile an anthology of sayings. The novel is full of perceptive observations about the evolving nature of relationships, the differences in attitudes between the generations, how productively (or not) we spend our time, and the challenges or fears of ageing. The heat and sensuality of an English summer are beautifully evoked.

The Pachinko Parlour by Elisa Shua Dusapin (tr. Aneesa Abbas Higgins)

A few years ago, I read and loved Winter in Sokcho, a beautiful, dreamlike novella that touched on themes of detachment, fleeting connections and the pressure to conform to societal norms. In 2022, Elisa Shua Dusapin returned with her second book, The Pachinko Parlour, another wonderfully enigmatic novella that shares many qualities with its predecessor. As in her previous work, Dusapin draws on her French-Korean heritage for Pachinko, crafting an elegantly expressed story of family, displacement, fractured identity and the search for belonging. Here we see people caught in the hinterland between different countries, complete with their respective cultures and preferred languages. It’s a novel that exists in the liminal spaces between states, the borders or crossover points from one community to the next and from one family unit to another. A wonderfully layered exploration of displacement, belonging and unspoken tragedies from times past, all played out in a claustrophobic atmosphere from the suffocating heat.

Uncle Paul by Celia Fremlin

First published in 1959 and recently reissued by Faber, Uncle Paul was Fremlin’s second book, and what a brilliant novel it is – a wonderfully clever exploration of what can happen when we allow our imagination to run wild and unfettered, conjuring up all sorts of nightmare scenarios from our fears and suspicions. On the surface, Uncle Paul could be the relatively innocent story of three sisters getting caught up in troublesome domestic matters during a seaside holiday. But in Fremlin’s hands, the story takes on a more sinister dimension, tapping into the siblings’ fears of murder and revenge. Fremlin is so adept at capturing the challenges of holidaying in the temperamental British summer, from the tension of being cooped up in a caravan with family members, to squabbles over what to do next, to the sense of pressure we feel to be outside enjoying ourselves at every moment, even if the weather is dreadful and all we want to do is to stay indoors. I loved this clever, skilfully executed exploration of fear and suspicion, very much in the style of Patricia Highsmith’s and Shirley Jackson’s domestic noirs laced with the social comedy of Barbara Pym. A shoo-in for my 2023 reading highlights.

The Venice Train by Georges Simenon (tr. Ros Schwartz)

There’s a touch of Patricia Highsmith about this highly compelling novella in which an ordinary man gets sucked into a nightmare scenario by a stranger on a train. When we first meet Justin Calmar, he is travelling home to Paris from his family holiday in Venice, having been called back early by his boss. During the journey, Justin falls into a conversation with an unknown man, who subsequently asks for a favour. Will Justin deliver a suitcase for this man while he waits for his connecting train in Lausanne? – a task that signals no end of trouble for Simenon’s protagonist. I won’t reveal how this compulsive novella plays out, other than to say it’s a very gripping read with a striking, unexpected conclusion. This is classic Simenon, complete with a brilliant premise and the author’s trademark internal psychological conflict. The oppressive August heat adds to Justin’s discomfort, dialling up the tension in this atmospheric book.

So, there we are. Let me know what you think of these books if you’ve read some of them or are considering reading any of them in the future. Perhaps you have a favourite summer book or two? Please feel free to mention them in the comments below.