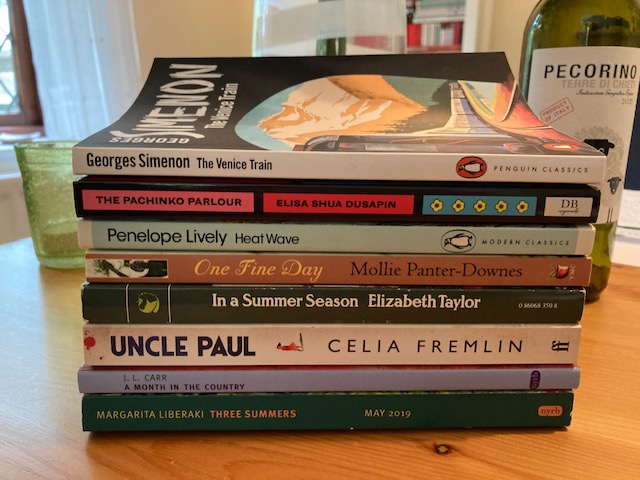

Vladivostok Circus is the latest of Elisa Shua Dusapin’s novels to appear in English, courtesy of the publishing arm of Daunt Books. Born in France and raised in Paris, Seoul and Switzerland, Dusapin is carving out a distinctive niche for herself with these slim, enigmatic novellas – the dreamlike Winter in Sokcho (published in English in 2020) is an excellent introduction to her style and themes, and the follow-up, The Pachinko Parlour, is equally compelling.

As a writer, Dusapin seems interested in exploring displacement, cross-cultural identities and fleeting connections, with her protagonists often finding themselves caught in the hinterlands between countries or states, existing in the liminal spaces that separate them from the surrounding world. There’s a similar sense of in-betweenness here too, giving the novella a recognisable ‘feel’, very much in tune with Dusapin’s earlier books. In fact, they could be seen as a loose trilogy in this respect.

This latest novel is narrated by twenty-two-year-old Nathalie, an aspiring costume designer newly arrived in Vladivostok for her first role after graduating in Belgium. She has come to Russia to design costumes for a trio of circus performers specialising in the Russian bar, a notoriously perilous discipline requiring immense levels of trust, precision and control.

Dusapin sets the novel’s ghostly, unsettling tone from the opening pages, with Nathalie arriving at the circus just as it is winding down for winter. The group’s Canadian director and safety technician, Leon – Nathalie’s contact for the role – doesn’t appear to be expecting her. Nevertheless, he hastily accommodates the newcomer as best he can until the other performers leave for the closed season. Here, Nathalie meets the Russian bar trio – the two bases, Anton and Nino (Russian and German respectively), who balance the bar on their shoulders; meanwhile, their Ukrainian ‘flyer’, Anna, is propelled through the air, spinning and somersaulting before again landing on the bar. The group will remain at the circus to prepare for a major competition in Ulan-Ude, where they will attempt to pull off four triple jumps in a row through a series of seamless manoeuvres.

As the story unfolds, we learn more about these individuals with different cultural backgrounds, each of whom seems to be dealing with their own personal challenges – from struggles with alcohol and complex family relationships to guilt over the consequences of an earlier accident. (The group’s previous flyer, Anton’s son, Igor, was seriously injured in a fall, a tragedy that has left its mark on his father – now in his mid-sixties and grappling with the impact of an ageing body.) Nathalie is also dealing with the aftermath of a broken relationship, having split with her boyfriend, Thomas, before embarking on the trip.

Something that Dusapin does particularly well here is to use the Russian bar to explore human relationships, especially the qualities needed to build deep and meaningful connections. The trio must work together in harmony, trusting one another implicitly to pull off a successful routine. As the flyer, Anna must relinquish control of her balance to Anton and Nino – a requirement that feels wildly counterintuitive, akin to the leap of faith we must take when developing relationships with others.

She [Anna] places a chair on the bar, balances it on two legs. They [Anton and Nino] hold it in place for as long as they can, barely moving a muscle. Sometimes Leon is there with me. He explains to me why exercises of this kind are so important: the flyer has to rely entirely on the bases for balance and not try to stabilise herself at all. Think of Anna as the chair, he says, that’s how passive she has to be. It’s one of the hardest things about the Russian bar discipline. (pp. 45–46)

Unsettled by her split from Thomas, Nathalie struggles to come to terms with this concept, especially at first. Nevertheless, in the novel’s most memorable scene, the others show her how it feels to stand freely on the bar, hoisting her up as if she were a flyer. Initially, an intuitive desire to stabilise herself kicks in; but with Anton’s and Nino’s encouragement, Nathalie surrenders control, tentatively jumping on the bar as the bases do their work. It’s a thrilling sensation for the newcomer to experience, winning the group’s respect and boosting her self-confidence.

After a false start with some wildly impractical initial designs, Nathalie ultimately hits on an inspired idea for the trio’s costumes, tapping into themes of propulsion, suspension, movement and gracefulness that underpin the routine. (The body is another recurring motif throughout the story, touching on each character’s perceptions of their body and the limitations it presents.)

An image is beginning to take shape in my mind. Anna’s skin, encrusted with shards of glass. Light glinting off the glass. All we see are the traces of her flight through the air. Gravity pulling her back down. Her shadow, then a flash. I begin to visualise a costume of lights. […]

Propulsion, suspension point, return to earth. It occurs to me that my materials can have an impact on their act too. Smoothing out the skin, tapering the body, enabling it to rise more quickly and to a greater height. And at the same time, accelerating the fall. (pp. 164-165)

Like Dusapin’s earlier work, this is not a plot-driven novel. Rather, the emphasis is on atmosphere, mood and cross-cultural connections. The liminal hinterland of the setting is vividly evoked, highlighting the unsettling, isolated quality of Vladivostok, particularly out of season.

I start walking back to the hotel, feeling ill at ease. Before, with all the activity of the circus, my being away from the others seemed less conspicuous. I look back at the circus building silhouetted against the night sky. Stars glinting, reflected in the glass dome. The posters around the entrance have already been taken down. From the street, the flesh-coloured rotunda looks strangely human in form. It reminds me of a torso. A light comes on in one of the rooms. Anna’s room. The men sleep on the courtyard side, overlooking the ocean. I picture Anna lit from behind, undressing, closing the curtains. The wind begins to swirl around me. I start to walk faster, pursued by a ray of moonlight. (p. 49)

Elsewhere in the novel, Dusapin highlights the city’s geographical location, close to the borders with China and North Korea, its shoreline ‘lined with fortress walls concealed in the rock face’. With military guns aimed firmly towards Japan, Vladivostok seems precariously placed, a city with one foot in Europe and another in Asia, while somehow feeling alien to both.

Military vessels ply back and forth under the great bridge. I screw up my eyes. It’s late afternoon, the light is fading, becoming more bleached out as the month progresses. In Europe, the light turns yellow; here, it has a translucent quality. Solid objects seem to lose density, matter becomes brittle, cracks appear – stone, glass, shale, trees. Dry cold. (p. 132)

While there are plenty of intriguing elements here, particularly the use of the Russian bar as a metaphor for human connections, I couldn’t help but feel that the novel falls somewhat short of the sum of its parts. Dusapin is operating in familiar territory here, particularly with the liminal nature of the setting, and I’m not sure how much it adds to her earlier books. Some readers may also feel underwhelmed by the story’s low-key ending, which lacks some of the alluring, enigmatic qualities of Sokcho and Pachinko. Nevertheless, there are some interesting insights into human nature here, alongside the eerie atmosphere, which is beautifully evoked.

‘I think people come to see if it’s all going to work,’ he [Nino] adds. ‘They want to see how far we can go. It’s easy to say they’re hoping for something magical but the truth is, what they really want is for something to go wrong. People find it reassuring to see others make mistakes.’ (p. 67)

The novel also contains some short extracts from a letter Nathalie writes to her father, a distant presence in her life at the time of the Vladivostok trip. These passages, which are interspersed with the other scenes, take place in the future, indicting how Nathalie’s life develops following her time with the circus. It’s an interesting addition to the story, highlighting the positive impact of this experience on her relationships with others.

All in all, an enjoyable, atmospheric read – and I look forward to seeing what Dusapin turns her hand to next, especially if she branches out into other, less familiar areas.

(My thanks to the publisher for kindly providing a review copy. This is my last post for Karen and Lizzy’s #ReadIndies project, which has been running throughout February.)