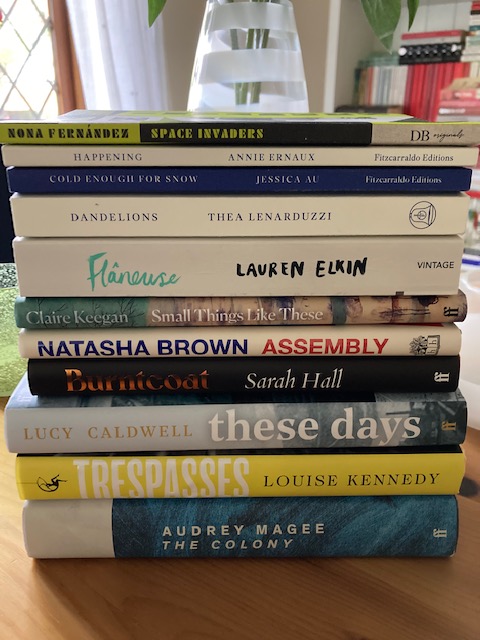

2022 has been another excellent year of reading for me. I’ve read some superb books over the past twelve months, the best of which feature in my reading highlights.

Just like last year, I’m spreading my books of the year across two posts – ‘recently published’ titles in this first piece, with older books (including reissues) to follow next week. Hopefully, some of you might find this list of contemporary favourites useful for last-minute Christmas gifts.

As many of you know, most of my reading comes from books first published in the mid-20th century. But this year, I’ve tried to read a few more newish books – a mixture of contemporary fiction and one or two memoirs/biographies. So, my books-of-the-year posts will reflect this mix. (I’m still reading more backlisted titles than new ones, but the contemporary books I chose to read this year were very good indeed. I’m also being quite liberal with my definition of ‘recently published’ as a few of my favourites first came out in their original language 10-15 years ago.)

Anyway, enough of the preamble! Here are my favourite recently published books from a year of reading. These are the books I loved, the books that have stayed with me, the books I’m most likely to recommend to other readers. I’ve summarised each one in this post (in order of reading), but you can find my full reviews by clicking on the appropriate links.

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Like many readers, I’ve been knocked sideways by Claire Keegan this year. She writes beautifully about elements of Ireland’s troubled social history with a rare combination of delicacy and precision; her ability to compress big themes into slim, jewel-like novellas is second to none. Set in small-town Ireland in the run-up to Christmas 1985, Small Things is a deeply moving story about the importance of staying true to your values – of doing right by those around you, even if it puts your family’s security and aspirations at risk. Probably the most exquisite, perfectly-formed novella I read this year – not a word wasted or out of place.

Assembly by Natasha Brown

Another very impactful, remarkably assured novella, especially for a debut. (I’m excited to see what Natasha Brown produces next!) Narrated by an unnamed black British woman working in a London-based financial firm, this striking book has much to say about many vital sociopolitical issues. Toxic masculinity, the shallowness of workplace diversity programmes, the pressure for people of colour to assimilate into a predominantly white society, and the social constructs perpetuating Britain’s damaging colonial history – they’re all explored here. I found it urgent and illuminating – a remarkable insight into how it must feel to be a young black woman in the superficially liberal sectors of society today.

These Days by Lucy Caldwell

Last year, Lucy Caldwell made my 2021 reading highlights with Intimacies, her nuanced collection of stories about motherhood, womanhood and life-changing moments. This year she’s back with These Days, an immersive portrayal of the WW2 bombing raids in the Belfast Blitz, seen through the eyes of a fictional middle-class family. What Caldwell does so well here is to make us care about her characters, ensuring we feel invested in their respective hopes and dreams, their anxieties and concerns. It’s the depth of this emotional investment that makes her portrayal of the Belfast Blitz so powerful and affecting to read. A lyrical, exquisitely-written novel from one of my favourite contemporary writers.

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au

At first sight, the story being conveyed in Cold Enough for Snow seems relatively straightforward – a mother and her adult daughter reconnect to spend some time together in Japan. Nevertheless, this narrative is wonderfully slippery – cool and clear on the surface, yet harbouring fascinating hidden depths within, a combination that gives the book a spectral, enigmatic quality, cutting deep into the soul. Au excels in conveying the ambiguous nature of memory, how our perceptions of events can evolve over time – sometimes fading to a feeling or impression, other times morphing into something else entirely, altered perhaps by our own wishes and desires. A meditative, dreamlike novella from a writer to watch.

Foster by Claire Keegan

I make no apologies for a second mention of Claire Keegan – she really is that good! As Foster opens, a young girl from Clonegal in Ireland’s County Carlow is being driven to Wexford by her father. There she will stay with relatives, an aunt and uncle she doesn’t know, with no mention of a return date or the nature of the arrangement. The girl’s mother is expecting a baby, and with a large family to support, the couple has chosen to take the girl to Wexford to ease the burden at home. Keegan’s sublime novella shows how the girl blossoms under the care of her new family through a story that explores kindness, compassion, nurturing and acceptance from a child’s point of view.

Happening by Annie Ernaux (tr. Tanya Leslie)

I’ve read a few of Ernaux’s books over the past 18 months, and Happening is probably the pick of the bunch (with Simple Passion a very close second). In essence, it’s an account of Ernaux’s personal experiences of an illegal abortion in the early ‘60s when she was in her early twenties – her quest to secure it, what took place during the procedure and the days that followed, all expressed in the author’s trademark candid style. What makes this account so powerful is the rigorous nature of Ernaux’s approach. There are no moral judgements or pontifications here, just unflinchingly honest reflections on a topic that remains controversial today. A really important book that deserves to be widely read, even though the subject matter is so raw and challenging.

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall

I adored this haunting, beautifully-crafted story of love, trauma, and the creation of art, all set against the backdrop of a deadly global pandemic. Hall’s novel explores some powerful existential themes. How do we live with the knowledge that one day we will die? How do we prepare for the inevitable without allowing it to consume us? And what do we wish to leave behind as a legacy of our existence? Intertwined with these big questions is the role of creativity in a time of crisis – the importance of art in the wake of trauma, both individual and collective. In Burntcoat, Sarah Hall has created something vital and vivid, capturing the fragile relationship between life and death – not a ‘pandemic’ novel as such, but a story where a deadly virus plays its part.

Flâneuse by Lauren Elkin

When we hear the word ‘flâneur’, we probably think of some well-to-do chap nonchalantly wandering the streets of 19th-century Paris, idling away his time in cafés and bars, casually watching the inhabitants of the city at work and play. Irrespective of the specific figure we have in mind, the flâneur is almost certainly a man. In this fascinating book, the critically-acclaimed writer and translator Lauren Elkin shows us another side of this subject, highlighting the existence of the female equivalent, the eponymous flâneuse. Through a captivating combination of memoir, social history and cultural studies/criticism, Elkin walks us through several examples of notable flâneuses down the years, demonstrating that the joy of traversing the city has been shared by men and women alike. A thoughtful, erudite, fascinating book, written in a style that I found thoroughly engaging.

Space Invaders by Nona Fernández (tr. Natasha Wimmer)

First published in Chile in 2013, this memorable, shapeshifting novella paints a haunting portrait of a generation of children exposed to the horrors of Pinochet’s dictatorship in the 1980s – a time of deep oppression and unease. The book focuses on a close-knit group of young adults who were at school together during the ‘80s and are now haunted by a jumble of disturbing dreams interspersed with shards of unsettling memories – suppressed during childhood but crying out to be dealt with now. Collectively, these striking fragments form a kind of literary collage, a powerful collective memory of the group’s absent classmate, Estrella, whose father was a leading figure in the State Police. Fernandez adopts a fascinating combination of form and structure for her book, using the Space Invaders game as both a framework and a metaphor for conveying the story. An impressive achievement by a talented writer – definitely someone to watch.

The Colony by Audrey Magee

Set on a small, unnamed island to the west of Ireland during the Troubles, The Colony focuses on four generations of the same family, highlighting the turmoil caused when two very different outsiders arrive for the summer. Something Magee does so brilliantly here is to move the point-of-view around from one character to another – often within the same paragraph or sentence – showing us the richness of each person’s inner life, despite the limited nature of their existence. In essence, the novel is a thought-provoking exploration of the damaging effects of colonisation – touching on issues including the acquisition of property, the demise of traditional languages and ways of living, cultural appropriation and, perhaps most importantly, who holds the balance of power in this isolated society. I found it timely, thoughtful and utterly compelling – very highly recommended indeed.

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy

Another excellent novel set during the Troubles, Trespasses is a quietly devastating book, steeped in the tensions of a country divided by fierce sectarian loyalties. It’s also quite a difficult one to summarise in a couple of sentences – at once both an achingly tender story of an illicit love affair and a vivid exploration of the complex network of divisions that can emerge in highly-charged communities. The narrative revolves around Cushla, a young primary teacher at a local Catholic school, and her married lover, Michael, a Protestant barrister in his early fifties. Here we see ordinary people living in extraordinary times, buffeted by a history of violence that can erupt at any moment. I loved this beautifully-written, immersive page-turner – it’s probably one of my top three books of the year.

Dandelions by Thea Lenarduzzi

In Dandelions, the Italian-born editor and writer Thea Lenarduzzi has given us a gorgeous, meditative blend of family memoir, political and socioeconomic history, and personal reflections on migration between Italy and the UK. Partly crafted from discussions between Thea and her paternal grandmother, Dirce, the book spans four generations of Lenarduzzi’s family, moving backwards and forwards in time – and between Italy and England – threading together various stories and vignettes that span the 20th century. In doing so, a multilayered portrayal of Thea’s family emerges, placed in the context of Italy’s sociopolitical history and economic challenges. Another book I adored – both for its themes and the sheer beauty of Lenarduzzi’s prose.

So that’s it for my favourite ‘recently published’ titles from a year of reading – I’d love to hear your thoughts below. Do join me again next week when I’ll be sharing the best older books I read this year with plenty of literary treasures still to come!