Over the past couple of years, I’ve put together a few themed posts on some of my favourite seasonal reads from the shelves. They were fun to compile, and several of you seemed to enjoy them, so I’ve been meaning to complete the annual cycle ever since. (If they’re of interest, you can find my autumn, winter and spring selections by clicking on the appropriate links.)

Now that we’re in July, I thought it would be timely to write about a few of my favourite summer reads. I always look forward to this season; the warm weather gives my hands a chance to recover somewhat from the harshness of winter. It’s also one of my favourite times of the year in fiction, rich with stories of holidays, the loss of innocence and various transgressions – hopefully my choices will reflect this!

A Wreath for the Enemy by Pamela Frankau

I love coming-of-age novels, stories where the central protagonist must navigate the tricky transition from adolescence to adulthood and all the attendant complexities this brings. Some of my favourites feature a defining moment, a life-changing event where the innocence or simplicity of youth is shattered, ushering in a new, more profound understanding of the wider world. That’s certainly the case in Pamela Frankau’s glorious 1954 novel A Wreath for the Enemy, brilliantly described by Norah Perkins (on Backlisted) as the love child of Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night. Elements of Brideshead Revisited and Bonjour Tristesse (see below) also spring to mind, especially for their atmosphere and mood. This wonderfully immersive coming-of-age story will almost certainly resonate with anyone who recalls the turmoil of adolescence, from the passions, tragedies and shattered illusions of youth to the growth that ultimately follows. Daunt Books have just reissued this one, perfectly timed for summer with its hot, passionate emotions and lush, sun-drenched mood.

Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan (tr. Irene Ash vs Heather Lloyd)

A quintessential summer read, Bonjour Tristesse is an irresistible story of love, frivolity and the games a young girl plays with other people’s emotions, the action playing out in the glamorous French Riviera. Seventeen-year-old Cécile is spending the summer on the Côte d’Azur with her father, Raymond, and his latest lover, Elsa. Everything is leisurely and glorious until another woman arrives on the scene, the glamorous and sophisticated Anne, whose very presence threatens to disrupt Cécile’s idyllic life with her father. Sagan’s novella is an utterly compelling read with a dramatic denouement. My review is based on Heather Lloyd’s 2013 translation, but if you’re thinking of reading this one. I would strongly recommend Irene Ash’s 1955 version – it’s more vivacious than the Lloyd, with a style that perfectly complements the story’s magical atmosphere and mood.

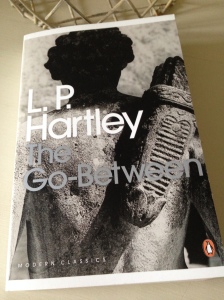

The Go-Between by L. P. Hartley

No self-respecting list of summer reads would be complete without The Go-Between, a compelling story of secrets, betrayals and the power of persuasion, set against the heady backdrop of the English countryside in July. Leo Colston (now in his sixties) recalls a fateful summer he spent at a school friend’s house in Norfolk some fifty years earlier, a trip that marked his life forever. The novel captures the pain of a young boy’s initiation into the workings of the adult world as Leo is caught between the innocence and subservience of childhood and the complexities of adulthood. Fully deserving of its status as a modern classic; the 1971 film adaptation, featuring Julie Christie and Alan Bates, is terrific, too!

Agostino by Alberto Moravia (tr. Michael F. Moore)

Another excellent novel about a young boy’s loss of innocence over a seemingly idyllic summer – in this instance, the setting is an Italian seaside resort in the mid-1940s. Moravia’s protagonist is Agostino, a thirteen-year-old boy who is devoted to his widowed mother. When his mother falls into a dalliance with a handsome young man, Agostino feels uncomfortable and confused by her behaviour, emotions that quickly turn to revulsion as the summer unfolds. This short but powerful novel is full of strong, sometimes brutal imagery. The murky, mysterious waters of the settings mirror the cloudy undercurrent of emotions in Agostino’s mind. Ultimately, this is a story of a young boy’s transition from the innocence of boyhood to a new phase in his life. While this should be a happy an exciting time of discovery for Agostino, the summer is marked by a deep sense of pain and confusion. A striking, evocative novella that deserves to be better known.

The Past by Tessa Hadley

A subtle novel of family relationships and tensions, written with real skill and psychological insight into character, The Past revolves around four adult siblings – Harriet, Alice, Fran and Roland – who come together for a three-week summer holiday at the Crane family home in Kington, deep in the English countryside. The siblings have joint ownership of the house, and one of their objectives during the trip is to decide the property’s fate. The inner life is each character is richly imagined, with Hadley moving seamlessly from one individual’s perspective to the next throughout the novel. Everything is beautifully described, from the characters’ preoccupations and concerns to the house and the surrounding countryside. A nearby abandoned cottage and its mysterious secrets are particularly vividly realised, adding to the sense of unease that pulses through the narrative.

The Island by Ana María Matute (tr. Laura Lonsdale)

I loved this one. Set on the island of Mallorca, shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, The Island is a darkly evocative coming-of-age narrative with a creeping sense of oppression. With her mother no longer alive and her father away in the war, Matia has been taken to the island to live with her grandmother (or ‘abuela’), Aunt Emilia and cousin Borja – not a situation she relishes. Matute excels in her depiction of Mallorca as an alluring yet malevolent setting, drawing on striking descriptions of the natural world to reinforce the impression of danger. It’s a brutal and oppressive place, torn apart by familial tensions and longstanding political divisions. As this visceral novella draws to a close, Matia is left with few illusions about the adult world. The beloved fables and fairy tales of her childhood are revealed to be fallacies, contrasting starkly with the duplicity, betrayal and cruelty she sees being played out around her. An unsettling summer read, one of my favourites in translation.

Last Summer in the City by Gianfranco Calligarich (tr. Howard Curtis)

Another wonderfully evocative read – intense, melancholic and richly cinematic, like a cross between Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and the novels of Alfred Hayes, tinged with despair. Set in Rome in the late 1960s, the novel follows Leo, a footloose writer, as he drifts around the city from one gathering to another, frequently hosted by his glamorous, generous friends. One evening, he meets Arianna, a beautiful, unpredictable, impulsive young woman who catches his eye; their meeting marks the beginning of an intense yet episodic love affair that waxes and wanes over the summer and beyond. Calligarich has given us a piercing depiction of a doomed love affair here. These flawed, damaged individuals seem unable to connect, ultimately failing to realise what they could have had together until that chance has gone, frittered away like a night on the tiles. This intense, expresso shot of a novella will likely resonate with those who have loved and lost.

Love and Summer by William Trevor

Set in the idyllic countryside of Ireland in the 1950s, Love and Summer is a gentle, contemplative novel about lost love and missed chances. Trevor perfectly captures the rhythm of life in a small farming community, the sort of place where everyone knows everyone else’s business, where any deviation from the expected norm is noticed and judged. It is a world populated by lonely, damaged people who expect little from life save for a simple existence with few opportunities or openings. Trevor’s prose is quietly beautiful – simple and unadorned, yet subtle enough to convey the depth of feeling at play. Last but by no means least, this novel is very highly recommended indeed.

Do let me know what you think of these books if you’ve read some of them already or if you’re considering reading any of them in the future. (I could have easily picked another half-dozen or so, there were so many to choose from!) Perhaps you have a favourite summer book or two? Please feel free to mention them in the comments below.