Like Yiyun Li, whose beguiling novel The Book of Goose I wrote about in January, Sara Baume has been on my radar for a few years, ever since the publication of her 2015 debut Spill Simmer Falter Wither to very positive reviews. Baume was born in Lancashire but grew up in County Cork – and it’s Ireland which forms the setting for her latest novel, Seven Steeples, recently longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize, an award dedicated to celebrating the creative talent of young writers worldwide. It’s a quiet, contemplative book – a beautifully-crafted story of withdrawal from conventional society for the peace of a minimalist existence. Alongside this central theme, the novel has much to say about the natural erosion that occurs over time, from the decay of buildings and possessions to the dwindling of human contact and relationships.

There is very little conventional action or plot here (too little for some readers, I suspect). Instead, Seven Steeples revolves around Sigh (Simon) and Bell (Isobel), ‘two solitary misanthropes’ who decide to dissociate themselves from their former lives, leaving their unfulfilling jobs and tenuous family connections to live together in a remote rented house by the Irish coast. The building – which has existed for seven decades, one of many significant ‘sevens’ in the book – sits in the shadow of a low mountain, an ever-watchful presence that looms large in Baume’s story.

Accompanied by their dogs, Voss, a ‘spry and devious’ terrier, and Pip, ‘a hulking, dull-witted’ lurcher, Sigh and Bell aim to share a simple existence, getting by on a combination of welfare payments and their meagre savings, far away from the bustle of the city. There is no romantic or sexual attraction here, simply a shared desire for a different way of life. Both have made the conscious decision to lose touch with their families and create a new one of their own, complete with Voss and Pip.

…they had each in their separate large families been persistently, though not unkindly, overlooked, and this had planted in Bell and in Sigh the amorphous idea that the only appropriate trajectory of a life was to leave as little trace as possible and incrementally disappear. (p. 18)

The novel follows Sigh, Bell and their dogs over seven years, capturing their regular practices and routines. Both individuals are creatures of habit, walking the same route every evening, paying close attention to any slight changes from the previous day. There is a simplicity and quiet beauty to their rituals, the daily walks with and without the dogs, weekly trips to the shops, and occasional interactions with a nearby farmer whose presence they find reassuring without feeling overly intrusive.

Over the seven years, the novel also captures the changing seasons, beginning in January in year one and moving through to December by year seven. There is some exquisite, poetic writing about the natural world here – often quite unusual in style, such as this description of a sycamore tree bursting into life in the midst of June.

The mess of twisted, whiskered limbs exploded against the horizon. Its profile went from a line drawing to a watercolour, from spiked and tapping to fluffed and murmuring. (p. 108)

Alongside the turning of the seasons, the weather often affects the couple’s days, guiding their rhythms to a certain extent. As I mentioned above, the writing is beautiful – full of vivid imagery, frequently expressed in a language of its own.

Weather systems arrived from the Atlantic and raced across their valley of sky. There was a vacillating rainbow, a paroxysm of wind, a spasmodic shower of hail. And then, the next day, there was an unbroken traffic jam of low-slung cloud backed up between the sea and the mountain, ironing the panorama away, moulting fine rain. (p. 43)

As the months and years slip by, Bell and Sigh gradually let the house fester and crumble around them. Crockery and glasses break, cutlery and utensils are lost, various appliances wear out or break down, the building itself degrades further. There is a palpable sense of erosion here, a steady decline that feels inevitable as it progresses. Yet, in pursuit of their isolated existence, with an unwillingness to ask for help or favours for fear of owing something in return, Bell and Sigh simply allow the house and its contents to degrade, continuing their natural trajectories of decay.

They had imagined, in the beginning, that if everything they owned was old and shoddy, even ugly, certainly nearing the end of its useful life, then they would better be able to bear its loss. (p. 163)

Occasionally, they debate whether to replace something that has broken down or been lost, typically without reaching an agreement – consequently, nothing gets done. Over the years, the detritus gradually piles up, a heady mix of particles of dust, hair, sand, dirt, pine needles, bodily fluids, flies, spiders, moths, mouse droppings and general clutter. There are cursory attempts to tidy up now and again, but these are superficial at best.

There was a bottomless supply of hair that flowed from the dogs, and dust from the ash that flowed from the fire, and they had combined – the dog hair and ash dust – into a new kind of matter, sticky, quilted. (p. 213)

From time to time, they discuss the remnants of family they have left behind, back in their former solitary lives, wondering aloud whether to contact them again, even if it means confronting the embarrassment of having allowed these relationships to slide. Nevertheless, the dilemma is inevitably settled by a lack of action, Bell and Sigh’s default mode when faced with situations where decisions are required.

They are scathing about the owners of holiday cottages, people who possess hundreds of things they rarely use, often with duplicates in their second homes. There are subtle references to environmental changes too, from the wildness of the weather to the increasing pressures of farming, with Baume eschewing idyllic imagery for the realities of rural life.

While the house is virtually a character in its own right, replete with a multitude of sounds, sights and smells, Bell and Sigh remain somewhat oblique and elusive – a little hard to pin down. At first, they seem quite different from one another, each with their own distinctive characteristics and habits; Bell, for instance, is the quicker of the two to anger, while Sigh has a seemingly endless ‘capacity for regret’. Over time, however, their personalities become increasingly similar, to the point where they even begin to resemble one another in physical appearance and dress as their clothes are pooled together.

Year after year, the mountain remains unclimbed, despite the pair’s initial intentions to tackle it one day. Finally, in their eighth year, they decide to climb it, revealing a poignant reflection that illuminates the rest of the book. Like Jessica Au’s meditative novella Cold Enough for Snow, Seven Steeples closes with the mention of something significant, a revelation of sorts that may prompt readers to question the true nature of the situation they see before them. It’s a clever, melancholy ending, likely to send some readers back to the novel’s early chapters, eager to revisit specific aspects of the text.

In summary, Seven Steeples is a subtle, elegantly structured story of withdrawal from conventional society, the rejection of consumerism and wider societal networks in favour of a minimalist life. Alongside this central theme, the novel depicts the natural erosion that occurs over time, from the decay of buildings and possessions to the dwindling of human contact and relationships. In truth, it’s a book I liked and admired rather than loved, but there’s no denying the beauty of Baume’s prose, especially when portraying the natural world. The book slips effortlessly between prose and a form of poetry, with the layout of words on the page reflecting something of the novel’s rhythm and recurring themes. A very accomplished book that will lend itself to different interpretations, especially towards the end.

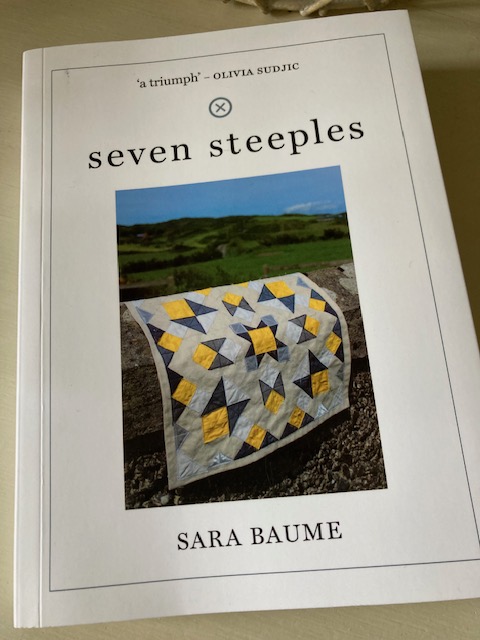

Seven Steeples is published by Tramp Press; personal copy