As some of you may know, July is Spanish Lit Month (#SpanishLitMonth), hosted by Stu at the Winstonsdad’s blog. It’s a month-long celebration of literature first published in the Spanish language – you can find out more about it here. In recent years, Stu and his sometimes co-host, Richard, have also included Portuguese literature in the mix, and that’s very much the case for 2021 too.

I’ve reviewed quite a few books that fall into the category of Spanish lit over the lifespan of this blog (although not so many of the Portuguese front). If you’re thinking of joining in and are looking for some ideas on what to read, here are a few of my favourites.

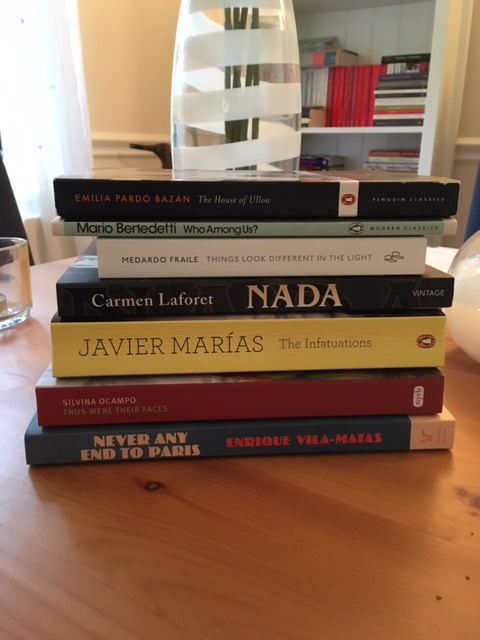

The House of Ulloa by Emilia Pardo Bazan (tr. Paul O’Prey and Lucia Graves)

This is a marvellous novel, a great discovery for me, courtesy of fellow Spanish Lit Month veteran, Grant from 1streading. The House of Ulloa tells a feisty tale of contrasting values as a virtuous Christian chaplain finds himself embroiled in the exploits of a rough and ready marquis and those of his equally lively companions. This classic of 19th-century Spanish literature is a joy from start to finish, packed full of incident to keep the reader entertained.

Who Among Us? by Mario Benedetti (tr. Nick Caistor)

This intriguing, elusive novella by the Uruguayan author and journalist, Mario Benedetti, uses various different forms to examine a timeless story of love and misunderstandings. We hear accounts from three different individuals embroiled in a love triangle. Assumptions are made; doubts are cast; and misunderstandings prevail – and we are never quite sure which of the three accounts is the most representative of the true situation, if indeed such a thing exists. Who among us can make that judgement when presented with these individuals’ perceptions of their relationships with others? This is a thoughtful, mercurial novella to capture the soul.

Sidewalks by Valeria Luiselli (tr. Christina McSweeney)

A beautiful collection of illuminating essays, several of which focus on locations, spaces and cities, and how these have evolved over time. Luiselli, a keen observer, is a little like a modern-day flâneur (or in one essay, a ‘cycleur’, a flâneur on a bicycle) as we follow her through the city streets and sidewalks, seeing the surroundings through her eyes and gaining access to her thoughts. A gorgeous selection of pieces, shot through with a melancholy, philosophical tone.

Things Look Different in the Light by Medardo Fraile (tr. Margaret Jull Costa)

Another wonderful collection of short pieces – fiction this time – many of which focus on the everyday. Minor occurrences take on a greater level of significance; fleeting moments have the power to resonate and live long in the memory. These pieces are subtle, nuanced and beautifully observed, highlighting situations or moods that turn on the tiniest of moments. While Fraile’s focus is on the minutiae of everyday life, the stories themselves are far from ordinary – they sparkle, refracting the light like the crystal chandelier in Child’s Play, one of my favourite pieces from this selection.

Nada by Carmen Laforet (tr. Edith Grossman)

Carmen Laforet was just twenty-three when her debut novel, Nada, was published. It’s an excellent book, dark and twisted with a distinctive first-person narrative. Here we see the portrayal of a family bruised by bitterness and suspicion, struggling to survive in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. This is a wonderfully evocative novel, a mood piece that captures the passion and intensity of its time and setting. Truly deserving of its status as a Spanish classic.

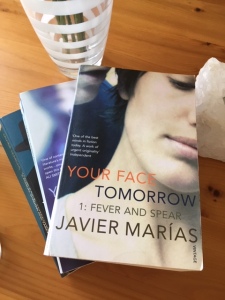

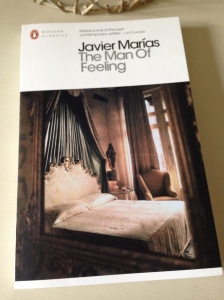

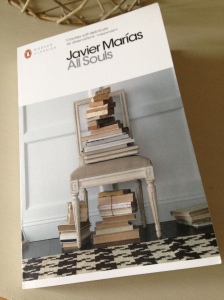

The Infatuations by Javier Marías (tr. Margaret Jull Costa)

My first Marías, and it remains a firm favourite. A man is stabbed to death in a shocking incident in the street, but this novel offers much more than a conventional murder mystery. In Marías’s hands, the story becomes an immersive meditation, touching on questions of truth, chance, love and mortality. The writing is wonderful – philosophical, reflective, almost hypnotic in style. Those long, looping sentences are beguiling, pulling the reader into a shadowy world, where things are not quite what they seem on at first sight.

Thus Were Their Faces by Silvina Ocampo (tr. Daniel Balderston)

I love the pieces in this volume of forty-two stories, drawn from a lifetime of Ocampo’s writing – the way they often start in the realms of normality and then tip into darker, slightly surreal territory as they progress. Several of them point to a devilish sense of magic in the everyday, the sense of strangeness that lies hidden in the seemingly ordinary. Published by NYRB Classics, Thus Were Their Faces is an unusual, poetic collection of vignettes, many of which blur the margins between reality and the imaginary world. Best approached as a volume to dip into whenever you’re in the mood for something different and beguiling.

Never Any End to Paris by Enrique Vila-Matas (tr. Anne McLean)

Vila-Matas travels to Paris where he spends a month recalling the time he previously spent in this city, trying to live the life of an aspiring writer – just like the one Ernest Hemingway recounts in his memoir, A Moveable Feast. Vila-Matas’ notes on this rather ironic revisitation are to form the core of an extended lecture on the theme of irony entitled ‘Never Any End to Paris’; and it is in this form that the story is presented to the reader. This is a smart, playful and utterly engaging novel, full of self-deprecating humour and charm.

Do let me know what you think of these books if you’ve read some of them. Hopefully, I’ll be able to fit in another couple of titles during the month, possibly more if the event is extended into August, as in recent years.

Maybe you have plans of your own for Spanish Lit Month – if so, what do you have in mind? Or perhaps you have a favourite book, first published in Spanish or Portuguese? Feel free to mention it alongside any other comments below.