2021 has been another tumultuous year for many of us – maybe not as horrendous as 2020, but still very challenging. In terms of books, various changes in my working patterns enabled me to read some excellent titles this year, the best of which feature in my highlights. My total for the year is somewhere in the region of 100 books, which I’m very comfortable with. This isn’t a numbers game for me – I’m much more interested in quality than quantity when it comes to reading!

This time, I’m spreading my books of the year across two posts – ‘recently published’ books in this first piece, with older titles to follow next week. As many of you will know, quite a lot of my reading comes from the 20th century. But this year, I’ve tried to read a few more recently published books – typically a mixture of contemporary fiction and some new memoirs/biographies. So, the division of my ‘books of the year’ posts will reflect something of this split. (I’m still reading more backlisted titles than new, but the contemporary books I chose to read this year were very good indeed. I’m also being quite liberal with my definition of ‘recently published’ as a few of my favourites came out in 2017-18.)

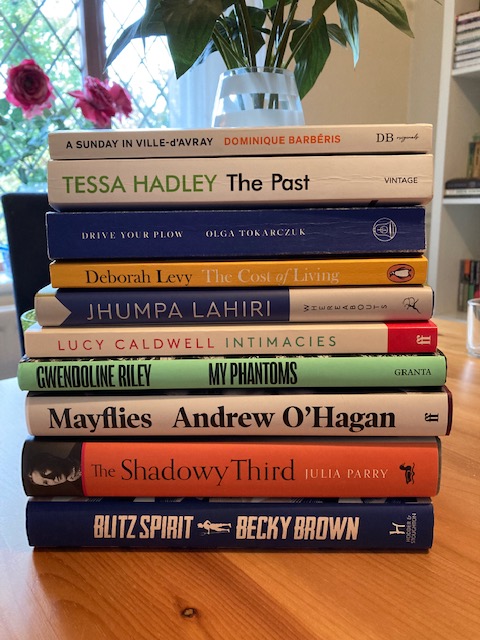

Anyway, enough of the preamble! Here are my favourite recently published books from a year of reading. These are the books I loved, the books that have stayed with me, the ones I’m most likely to recommend to other readers. I’ve summarised each one in this post (in order of reading), but you can find the full reviews by clicking on the appropriate links.

Mayflies by Andrew O’Hagan

Every now and again, a book comes along that catches me off-guard – surprising me with its emotional heft, such is the quality of the writing and depth of insight into human nature. Mayflies, the latest novel from Andrew O’Hagan, is one such book – it is at once both a celebration of the exuberance of youth and a love letter to male friendship, the kind of bond that seems set to endure for life. Central to the novel is the relationship between two men: Jimmy Collins, who narrates the story, and Tully Dawson, the larger-than-life individual who is Jimmy’s closest friend. The novel is neatly divided into two sections: the first in the summer of ’86, when the boys are in their late teens/early twenties; the second in 2017, which finds the pair in the throes of middle age. There are some significant moral and ethical considerations being explored here with a wonderful lightness of touch. An emotionally involving novel that manages to feel both exhilarating and heartbreaking.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk (tr. Antonia Lloyd-Jones)

A very striking novel that is by turns an existential murder mystery, a meditation on life in an isolated, rural community, and, perhaps most importantly, an examination of our relationship with animals and their place in the hierarchy of society. That might make Plow sound heavy or somewhat ponderous; however, nothing could be further from the truth! This is a wonderfully accessible book, a metaphysical novel that explores some fascinating and important themes in a highly engaging way. Arresting, poetic, mournful, and blacky comic, Plow subverts the traditional expectations of the noir genre to create something genuinely thought-provoking and engaging. The eerie atmosphere and sense of isolation of the novel’s setting – a remote Polish village in winter – are beautifully evoked.

The Shadowy Third by Julia Parry

When Julia Parry comes into possession of a box of letters between her maternal grandfather, the author and academic, Humphry House, and the esteemed Anglo-Irish writer, Elizabeth Bowen, it sparks an investigation into the correspondence between the two writers. Their relationship, it transpires, was an intimate, clandestine one (Humphry was married to Madeline, Parry’s grandmother at the time), waxing and waning in intensity during the 1930s and ‘40s. What follows is a quest on Parry’s part to piece together the story of Humphry’s relationship with Bowen – much of which is related in this illuminating and engagingly written book. Partly a collection of excerpts from the letters, partly the story of Parry’s travels to places of significance to the lovers, The Shadowy Third is a fascinating read, especially for anyone interested in Bowen’s writing. (It was a very close call between this and Paula Byrne’s Pym biography, The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, but the Parry won through in the end.)

The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy

This luminous meditation on marriage, womanhood, writing and reinvention is the second part of Deborah Levy’s ‘living autobiography’ trilogy – a series which commenced in 2014 with Things I Don’t Want to Know. In essence, this fascinating memoir conveys Levy’s reflections on finding a new way to live following the breakdown of her marriage after twenty or so years, prompting her to embrace disruption as a means of reinvention. Levy has a wonderful ability to see the absurdity in day-to-day situations, frequently peppering her reflections with irony and self-deprecating humour.

This is an eloquent, poetic, beautifully structured meditation on so many things – not least, what should a woman be in contemporary society? How should she live?

A Sunday in Ville-d’Avray by Dominique Barbéris (tr. John Cullen)

This beautiful, evocative novella is set in Paris on a Sunday afternoon in September, just at the crossover point between summer and autumn. The narrator – an unnamed woman – drives from the city centre to the Parisian suburb of Ville-d’Avray to visit her married sister, Claire Marie. As the two sisters sit and chat in the garden, an intimate story emerges, something the two women have never spoken about before. Claire Marie reveals a secret relationship from her past, a sort of dalliance with a mysterious man whom she met at her husband’s office. What emerges is a story of unspoken desire, missed opportunities and avenues left unexplored. This haunting, dreamlike novella is intimate and hypnotic in style, as melancholy and atmospheric as a dusky autumn afternoon.

Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri (tr. by the author)

This slim, beautifully constructed novella is an exploration of solitude, a meditation on aloneness and the sense of isolation that can sometimes accompany it. The book – which Lahiri originally wrote in Italian and then translated into English – is narrated by an unnamed woman in her mid-forties, who lives in a European city, also nameless but almost certainly somewhere in Italy. There’s a vulnerability to this single woman, a fragility that gradually emerges as she goes about her days, moving from place to place through a sequence of brief vignettes. As we follow this woman around the city, we learn more about her life – things are gradually revealed as she reflects on her solitary existence, sometimes considering what might have been, the paths left unexplored or chances that were never taken. This is an elegant, quietly reflective novella – Lahiri’s prose is precise, poetic and pared-back, a style that feels perfectly in tune with the narrator’s world.

The Past by Tessa Hadley

A subtle novel of family relationships and tensions, written with real skill and psychological insight into character, The Past revolves around four adult siblings – Harriet, Alice, Fran and Roland – who come together for a three-week holiday at the Crane family home in Kington, deep in the English countryside. The siblings have joint ownership of the house, and one of their objectives during the trip is to decide the property’s fate. The inner life of each individual is richly imagined, with Hadley moving seamlessly from one individual’s perspective to the next throughout the novel. Everything is beautifully described, from the characters’ preoccupations and concerns, to the house and the surrounding countryside. A nearby abandoned cottage and its mysterious secrets are particularly vividly realised, adding to the sense of unease that pulses through the narrative. My first by Hadley, but hopefully not my last.

Intimacies by Lucy Caldwell

A luminous collection of eleven stories about motherhood – mostly featuring young mothers with babies and/or toddlers, with a few focusing on pregnancy and mothers to be. Caldwell writes so insightfully about the fears young mothers experience when caring for small children. With a rare blend of honesty and compassion, she shows us those heart-stopping moments of anxiety that ambush her protagonists as they go about their days. Moreover, there is an intensity to the emotions that Caldwell captures in her stories, a depth of feeling that seems utterly authentic and true. By zooming in on her protagonists’ hopes, fears, preoccupations and desires, Caldwell has found the universal in the personal, offering stories that will resonate with many of us, irrespective of our personal circumstances.

Blitz Spirit by Becky Brown

In this illuminating book, Becky Brown presents various extracts from the diaries submitted as part of the British Mass-Observation project during the Second World War. (Founded in 1937, Mass-Observation was an anthropological study, documenting the everyday lives of ordinary British people from all walks of life.) The diary extracts presented here do much to debunk the nostalgic, rose-tinted view of the British public during the war, a nation all pulling together in one united effort. In reality, people experienced a wide variety of human emotions, from the novelty and excitement of facing something new, to the fear and anxiety fuelled by uncertainty and potential loss, to instances of selfishness and bickering, particularly as restrictions kicked in. Stoicism, resilience and acts of kindness are all on display here, alongside the less desirable aspects of human behaviour, much of which will resonate with our recent experiences of the pandemic.

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

A brilliantly observed, lacerating portrayal of a dysfunctional mother-daughter relationship that really gets under the skin. Riley’s sixth novel is a deeply uncomfortable read, veering between the desperately sad and the excruciatingly funny; and yet, like a car crash unfolding before our eyes, it’s hard to look away. The novel is narrated by Bridget, who is difficult to get a handle on, other than what she tells us about her parents, Helen (aka ‘Hen’) and Lee. This fascinating character study captures the bitterness, pain and irritation of a toxic mother-daughter relationship with sharpness and precision. The dialogue is pitch-perfect, some of the best I’ve read in recent years, especially when illustrating character traits – a truly uncomfortable read for all the right reasons.

And finally, a few honourable mentions for the books that almost made the list:

- Second Sight – an eloquent collection of film writing by the writer and critic, Adam Mars-Jones;

- Nomadland – Jessica Bruder’s eye-opening account of nomad life in America;

- Open Water – Caleb Azumah Nelson’s poetic, multifaceted novella;

- and The Years – Annie Ernaux’s impressive collective biography (tr. Alison L. Strayer), a book I admired hugely but didn’t love as much as others.

So that’s it for my favourite recently published titles from a year of reading. Do let me know your thoughts below – and join me again next week when I’ll be sharing my favourite ‘older’ books with plenty of treats still to come!