This is a post I’ve been meaning to put together for a while, a celebration of my favourite novels set in hotels. There’s something particularly fascinating about this type of location as a vehicle for fiction – a setting that brings together a range of different individuals who wouldn’t normally encounter one another away from the hotel. Naturally, there’s some potential for drama as various guests and members of staff mingle with one another, especially in the communal areas – opportunities the sharp-eyed writer can duly exploit to good effect.

While some guests will be holidaying at the hotels, others may be there for different reasons – travellers on business trips, for instance, or people recovering from illness or some other kind of trauma. Then we have the hotel staff and long-term residents, more permanent fixtures in the hotel’s fabric, so to speak. All have interesting stories to tell, irrespective of their positions. So here are a few of my favourites from the shelves.

Grand Hotel by Vicki Baum (1929 – tr. Basil Creighton)

Perhaps the quintessential hotel novel, this engaging story revolves around the experiences of six central characters as they brush up against one another in this glamorous Berlin setting. There are moments of significant darkness amid the lightness as Baum skilfully weaves her narrative together, moving from one individual to another with consummate ease – her characterisation is particularly strong. At the novel’s centre is the idea that sometimes our lives can change direction in surprising ways as we interact with others. As these characters come and go from the hotel, we see fragments of their lives – some are on their way up and are altered for the better, while others are less fortunate and emerge diminished. A thoroughly captivating gem with an evocative Weimar-era setting!

The Feast by Margaret Kennedy (1950)

Part morality tale, part mystery, part family saga/social comedy, Kennedy’s delightful novel was reissued last year by Faber in a fabulous new edition. This very cleverly constructed story – which takes place at The Pendizack cliffside hotel, Cornwall, in the summer of 1947 – unfolds over the course of a week, culminating in a dramatic picnic ‘feast’, Kennedy draws on an inverted structure, revealing part of her denouement upfront, while omitting crucial details about a fatal disaster. Consequently, the reader is in the dark as to who dies and who survives the tragedy until the novel’s end. What Kennedy does so well here is to weave an immersive story around the perils of the seven deadly sins, into which she skilfully incorporates the loathsome behaviours of her characters – both guests and members of staff alike. A wonderfully engaging book with some serious messages at its heart.

Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner (1984)

Another big hitter here, and one of my favourites in the list. As this perceptive novel opens, Edith Hope – an unmarried writer of romantic fiction – has just been packed off by her respectable, interfering friends to the Hotel du Lac, a rather austere establishment of high repute in the Swiss countryside. Right from the start, it’s clear that Edith has been banished from her sector of society, sent away to reflect on her misdemeanours, to ‘become herself again’ following some undisclosed scandal. (The reason for Edith’s exile is eventually revealed, but not until the last third of the book.) Central to the novel is the question of what kind of life Edith can carve out for herself, a dilemma that throws up various points for debate. Will she return to her solitary existence at home, complete with its small pleasures and its sense of freedom and independence? Or will she agree to compromise, to marry for social acceptability if not love? You’ll have to read the book itself to find out…

Mrs Eckdorf in O’Neill’s Hotel by William Trevor (1969)

We’re in much darker territory here with William Trevor, a writer whose work I’ve been reading steadily over the past four or five years. Mrs Eckdorf is very much of a piece with Trevor’s other novels from the 1970s – sad, somewhat sinister and beautifully observed. The novel’s catalyst is the titular Mrs Eckdorf – a most annoying and invasive woman who has fashioned a career as a photographer, exploiting the lives of unfortunate individuals around the world, their existences touched by devastation. With her nose for tragedy and a potentially lucrative story, Trevor’s protagonist inveigles her way into the Sinnott family, just in time for a landmark birthday celebration for the hotel’s owner, the elderly Mrs Sinnott. Once again, William Trevor proves himself a master of the tragicomedy, crafting a story that marries humour and poignancy in broadly equal measure.

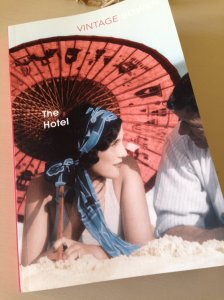

The Hotel by Elizabeth Bowen (1927)

Bowen’s striking debut is a story of unsuitable attachments – more specifically, the subtle power dynamics at play among various privileged guests holidaying at a high-class hotel on the Italian Riviera. The narrative revolves around Sydney Warren, a somewhat remote yet spirited young woman in her early twenties, and the individuals she meets on her trip. In some instances, the characters are gravitating towards one another for convenience and perhaps a vague kind of protection or social acceptability, while in others, there are more underhand motives at play. It all feels incredibly accomplished for a debut, full of little observations on human nature and the social codes that dictate people’s behaviour – there are some particularly wonderful details on hotel etiquette here. If you like Edith Wharton’s ‘society’ novels, The Hotel may well appeal.

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor (1971)

One of my all-time favourite novels, Mrs Palfrey is a something of a masterpiece, marrying bittersweet humour with a deeply poignant thread. In essence Taylor’s story follows a recently widowed elderly lady, Mrs Palfrey, as she moves into London’s Claremont Hotel. Here she joins a group of long-term residents in similar positions to herself, each one likely to remain there until illness intervenes and a move to a nursing home or hospital can no longer be avoided. This is a beautiful, thought-provoking novel, prompting the reader to consider the emotional and physical challenges of ageing – more specifically, our need to participate in life, the importance of small acts of kindness and the desire to feel valued, irrespective of our age. Taylor’s observations of social situations and the foibles of human nature are spot-on – there are some wonderfully funny moments here amid the poignancy and sadness. An undisputed gem that reveals more on subsequent readings, especially as we grow older ourselves.

Other honourable mentions include the following books:

- Rosamond Lehmann’s marvellous The Weather in the Streets (1936), in which the devastation of Olivia and Rollo’s doomed love affair plays out against the backdrop of dark, secluded restaurants and stuffy, sordid hotels;

- Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky (1949), a powerful, visceral novel set in the squalid towns and desert landscapes of North Africa in the years following the end of the Second World War. As Port and Kit Moresby (Bowles’ troubled protagonists) travel across the stiflingly hot desert, the hotels grow more sordid with each successive move, putting further strain on the couple’s fractured marriage;

- Finally, there’s Strange Hotel (2020), Eimear McBride’s immersive, enigmatic novel, where inner thoughts and self-reflections are more prominent than narrative and plot.

Do let me know your thoughts if you’ve read any of these books (you can buy most of them here via Bookshop.Org, together with a few other suggestions). Or maybe you have some favourite hotel novels that you’d like to share with others – I’m sure there are many more I’ve yet to discover, so please feel free to mention them below.

PS I’m also planning to do a ‘boarding house’ version of this post at some point, something that will come as no surprise to those who know me well!