This year, I’m spreading my 2023 reading highlights across a couple of posts. The first piece, on my favourite ‘recently published’ titles, is here, while this second piece puts the spotlight on the best ‘older’ books I read this year, including reissues of titles first published in the 20th century.

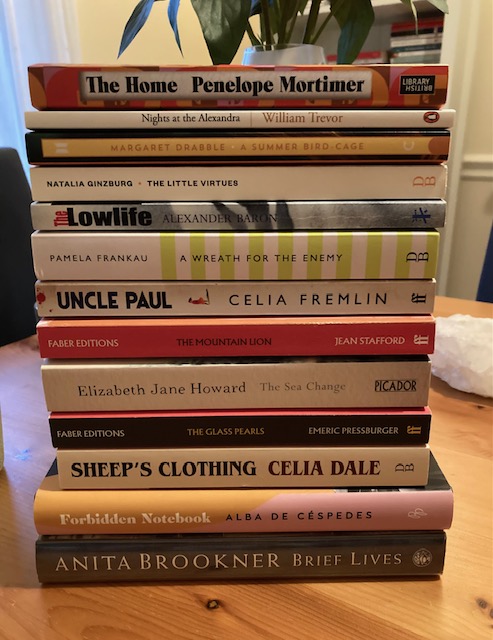

These are the books I loved, the books that have stayed with me, the ones I’m most likely to recommend to other readers. I’ve summarised each one in this post (in order of reading), but as before, you can find the full reviews by clicking on the appropriate links. There are thirteen in total – a Baker’s Dozen of wonderful vintage books!

The Little Virtues by Natalia Ginzburg (1962, tr. Dick Davis 1985)

I adored this thought-provoking collection of essays; it’s full of the wisdom of life. Ginzburg wrote these pieces individually between 1944 and 1962, and many were published in Italian journals before being grouped together here. In her characteristically lucid prose, Ginzburg writes of families and friendships, of virtues and parenthood, and of writing and relationships. Reading these pieces, we get a sense of how the author approaches her subjects obliquely or at an angle. In short, by writing about one aspect of a topic, Ginzburg triggers reverberations elsewhere – like an echo reverberating around the landscape or stone skimming across a pond – adding a broader resonance to her insights beyond their immediate sphere. It’s a fascinating collection, a keeper for the bedside table as a balm for the soul.

The Lowlife by Alexander Baron (1963)

Baron’s 1963 novella is an entertaining, picaresque story of a likeable Jewish charmer with a penchant for Emile Zola and a somewhat tortuous past. The anti-hero in question is forty-five-year-old Harryboy Boas, a lovable rogue with a conscience who feeds his gambling addiction with occasional stints as a Hofmann presser in the East End rag trade. Harryboy likes nothing more than a bit of peace and quiet, allowing him to read Zola novels all day in his room at Mr Siskin’s Hackney boarding house, preferably untroubled by the need to work. At night, he’s usually to be found at the local dog tracks, gambling away what little money he has, but everything changes when a new family, the Deaners, move in, a development that disturbs the relative calm and familiarity of Harryboy’s world. In short, this is a marvellous addition to the boarding house genre and a wonderful evocation of post-war London life.

Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Cespedes (1952, tr. Ann Goldstein 2023)

A remarkable rediscovered gem of Italian literature, a candid, exquisitely-written confessional from an evocative feminist voice. The novel is narrated by forty-three-year-old Valeria, who documents her inner thoughts in a secret notebook with great candour and clarity, laying bare her world with all its demands and preoccupations. For Valeria, the act of writing becomes a disclosure, an outlet for her frustrations with the family – her husband Michele, a somewhat remote but dedicated man, largely wrapped up in his own interests, which Valeria doesn’t share, and their two grown-up children who live at home. As the diary entries build up, we see how Valeria has been defined by the familial roles assigned to her; nevertheless, the very act of keeping the notebook leads to a gradual reawakening of her desires as she finds her voice, challenging the founding principles of her life with Michele. I adored this illuminating exploration of a woman’s right to her own existence in the face of competing demands; it’s probably my favourite book of the year.

Nights at the Alexandra by William Trevor (1987)

William Trevor is frequently cited as a master of the short story, and rightly so. His stories are spellbinding – humane, compassionate and beautifully written. He has a way of getting into the hearts and minds of his characters with insight and precision, laying bare their deepest preoccupations for the reader to see. These skills are very much in evidence in Nights at the Alexandra, a slim collection comprising the titular novella and two short stories. In the novella, fifty-eight-year-old Harry looks back on the days of his youth during WW2, when at the age of fifteen, he formed an unlikely but deeply touching friendship with Frau Messinger, a young Englishwoman who moved to Ireland with her much older German husband. This is a sad, melancholy story, but as Harry looks back at his life, he feels no regret. His memories of Frau Messinger are enough, shot through with happiness despite the spectre of loss. Likewise, the two short stories touch on broadly similar themes. These are quietly devastating tales of everyday country folk caught between the pull of their own desires and the familial duties that bind them to home. Trevor’s prose is exquisite and perfectly judged.

The Home by Penelope Mortimer (1971)

This perceptive semi-autobiographical novel follows an attractive but vulnerable middle-aged woman, Eleanor Strathearn, in the months following the breakdown of her marriage as she attempts to establish some kind of life for herself, while also delving into the meaning of ‘home’ with all its various connotations. The story opens with Eleanor and her youngest child, fifteen-year-old Philip, moving from their longstanding family home in London to a smaller residence near St John’s Wood. As her other grown-up children have flown the nest, Eleanor approaches her new life with a strange mix of emotions, oscillating wildly between stoic optimism and crushing grief – the latter largely winning out. Alongside the sadness, this excellent, slightly off-kilter novel has flashes of darkly comic humour throughout. Fans of Muriel Spark would likely enjoy this one, and possibly Elizabeth Taylor, too.

The Sea Change by Elizabeth Jane Howard (1959)

The more I read Elizabeth Jane Howard, the more I enjoy her. Subtle, perceptive and elegantly written, her novels frequently delve into the complexities of troubled marriages, and that’s very much the case here. At first sight, this story may seem very familiar – a successful, married middle-aged man falls for a young, attractive ingénue. However, Howard creates such a fascinating set-up, featuring four distinctive, fully fleshed-out characters, that somehow this classic narrative seems fresh and alive. The story revolves around four central figures: Emmanuel Joyce, a successful playwright in his early sixties; his glamorous but fragile wife, Lillian, who is twenty years younger than her husband; Emmanuel’s long-suffering business manager/rescuer, Jimmy Sullivan; and nineteen-year-old Alberta, newly-appointed to the role of Emmanuel’s secretary. This richly textured ensemble piece encompasses the tensions between familial responsibility and personal desire, the dissection of a failing marriage, and the fallout from losing a child. The novel also demonstrates how our lives can turn in an instant, altering our future trajectories in significant and surprising ways.

A Wreath for the Enemy by Pamela Frankau (1954)

A thoroughly immersive coming-of-age novel, brilliantly described by Norah Perkins (on Backlisted) as the love child of Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night. Elements of Brideshead Revisited and Bonjour Tristesse also spring to mind, especially for their atmosphere and mood. Central to the story is Penelope Wells, a precocious teenager who spends the school holidays with her bohemian father, Francis, and stepmother, Jeanne, in their small hotel on the balmy French Riviera. When the prim, middle-class Bradley family rent the neighbouring villa, Penelope is fascinated by the new arrivals, but the friendship she develops with young Don Bradley soon comes crashing down. The writing sparkles with just the right balance of humanity, insight and wit, perfectly capturing the intensity of the characters’ emotions as the drama plays out. A wonderful summer read that takes some surprising turns.

A Summer Bird-Cage by Margaret Drabble (1963)

This thoughtful, witty debut novel features an intelligent, educated young woman trying to find her place in an evolving world. Drabble focuses on two well-educated sisters here – twenty-one-year-old Sarah Bennett and her older sister, Louise, both Oxford-educated – exploring their different values and preoccupations. While Louise opts for marriage to Stephen, a wealthy but snobbish writer, Sarah tries to figure out what to do with her life. The writing is marvellous, encompassing chic 1960s fashions, hairstyles, and lifestyles, plus glimpses of Louise’s honeymoon in Rome. Drabble also gives us some wonderfully evocative descriptions of London, from Sarah waiting in the pouring rain to catch a bus at Aldwych to the messy glamour of backstage life in the city’s West End. A witty, hugely enjoyable book, shot through with some amusing touches, always beautifully judged.

Uncle Paul by Celia Fremlin (1959)

A wonderfully clever portrayal of what can happen when we allow our imagination to run wild and unfettered, conjuring up all sorts of nightmare scenarios from our fears and suspicions. On the surface, Uncle Paul could be the relatively innocent story of three sisters getting caught up in troublesome domestic matters during a seaside holiday. But in Fremlin’s hands, this narrative takes on a more sinister dimension, tapping into the siblings’ fears of murder and revenge. In short, this is an utterly brilliant novel, a clever, skilfully executed exploration of fear and suspicion, very much in the style of Patricia Highsmith’s and Shirley Jackson’s domestic noirs, laced with the social comedy of Barbara Pym. The seaside setting, complete with a creepy rundown holiday cottage, is beautifully evoked.

The Mountain Lion by Jean Stafford (1947)

If Carson McCullers and Elspeth Barker (of O Caledonia fame) had run off to the Colorado mountains to work on a novel, this rediscovered gem might have been the result! It’s a haunting, unnerving portrayal of a close but volatile brother-sister relationship, laced with an undercurrent of menace as adolescence beckons on the horizon. Stafford has created such an evocative, relatable world here, instantly recognisable to anyone who recalls the pain and awkwardness of adolescence – from the disdain we have for our parents and elders to the discomfort we feel in our bodies as they develop, to the confusion and resentments that frequently surface as we grow apart from our soulmates. She also infuses the narrative with an ominous sense of mystery, something poisonous and unknowable, especially towards the end.

Sheep’s Clothing by Celia Dale (1988)

Last year, Celia Dale made my annual highlights with A Helping Hand, an icily compelling tale of greed and deception, stealthily executed amidst carefully orchestrated conversations and kindly cups of tea. This year, she’s back with another gripping novel in a very similar vein. The central protagonist is Grace, a merciless, well-organised con woman in her early sixties with a track record of larceny. As a trained nurse with experience of care homes, Grace is well versed in the habits and behaviours of the elderly – qualities that have enabled her to develop a seemingly watertight plan for fleecing some of society’s most vulnerable individuals, typically frail old women living on their own. To enact her plan, Grace teams up with Janice, a passive, malleable young woman she met in Holloway prison. Together, the two women trick their victims in a cruel, callous way, worming their way into people’s homes by posing as Social Services. Another masterful, sinister novel from Celia Dale – all the more terrifying for its grounding in normality.

Brief Lives by Anita Brookner (1990)

In this penetrating character study novel, Brookner explores a demanding, codependent relationship between two women, Fay and Julia, thrown together by the business partnership between their respective husbands. Once a glamorous actress with Vogue features under her belt, Julia retains delusions of grandeur, thriving on an audience to pander to her whims. At heart, she is selfish, dismissive, cruel and sardonic, maintaining a hold over Fay (and other lonely, suggestible women) by manipulating them rather skilfully. While Fay dislikes Julia and her methods, she struggles to extricate herself from this woman’s grip, partly out of pity and partly from a strange sense of compulsion and duty. There’s a Bette Davis–Joan Crawford vibe to the toxic, codependent bond between Julia and Fay, reminiscent of the sisters’ relationship in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, albeit in a different context. I’m reading Brookner in publication order, and it’s one of my favourites to date.

The Glass Pearls by Emeric Pressburger (1966)

I loved this utterly gripping novel with a morally ambiguous German character at its heart. Central to the story, which is set in the mid-1960s, is Karl Braun, a cultured, mild-mannered German émigré working as a piano tuner in London. On the surface, Braun’s work colleagues and fellow lodgers assume their friend came to England to escape the Nazis. However, the more we read, the more we realise that Pressburger’s protagonist is haunted by the past. His wife and child perished in an Allied bombing raid over Hamburg – a tragic incident that might well have killed Braun himself had he not rushed to work that day to attend to pressing business. Soon, other more sinister details emerge, creating the impression that Braun is in hiding from something – or possibly someone – with a link to his past. As the narrative unfolds, this quiet story of an émigré trying to make his way in 1960s London morphs into a noirish thriller, the tension escalating with every turn of the page. A complex, deeply unnerving read that will test the reader’s sympathies in unexpected ways.

So, that’s it for my favourite books from another year of reading. Do let me know your thoughts on my choices – I’d love to hear your views.

All that remains is for me to wish you a very Merry Christmas and all the best for the year ahead – may it be filled with lots of excellent books, old and new!