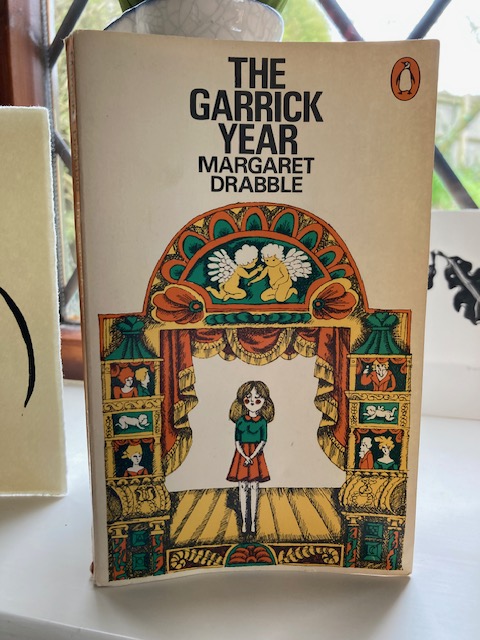

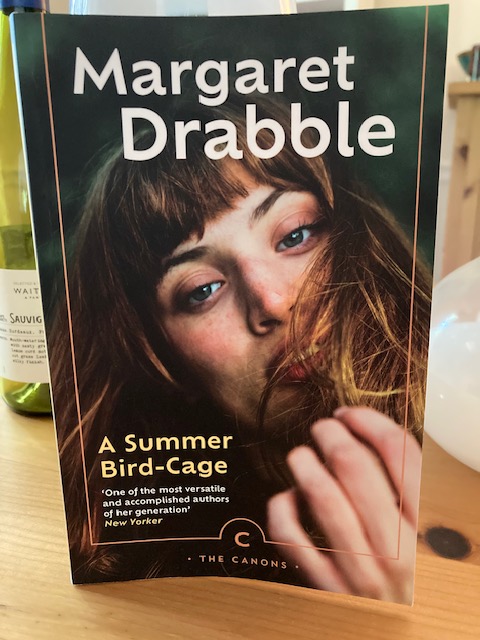

First published in 1964, The Garrick Year was Margaret Drabble’s second novel, nicely placed between her debut A Summer Bird-Cage (which I loved) and The Millstone (which I have in my TBR). It’s a brilliant, sharply observed book which explores how women’s lives in this era were frequently dictated by the demands of marriage and motherhood, irrespective of any personal ambitions and desires these individuals may have held. We are firmly in the early ‘60s here, when young women were beginning to question these traditional societal expectations while still feeling the pressure to conform.

Drabble’s heroine and narrator is Emma Evans, a spiky, city-loving mother and former model in her mid-twenties. Emma has been married to David, a self-centred young actor, for three years, and they have two children together – Flora, still a toddler, and baby Joe. From the outset, the couple’s relationship has been characterised by ‘provocation and bargaining for domination’, with barbed, wryly amusing exchanges being the order of the day.

Just as Emma is contemplating a return to work in a pioneering, part-time role as TV newsreader – a job she would dearly love to do – David announces a new opportunity of his own. The respected theatre director Wyndham Farrar has approached him to appear in a season of plays at Hereford’s Garrick Theatre. Naturally, David wishes to accept, expecting Emma to put her needs and ambitions aside in favour of his own.

I could hardly believe that marriage was going to deprive me of this too. It had already deprived me of so many things which I had childishly overvalued: my independence, my income, my twenty-two inch waist, my sleep, most of my friends who had deserted on account of David’s insults, a whole string of finite things, and many more indefinite attributes like hope and expectation. (p. 10)

So, while David prattles on about the charms of country living – green fields, cows, peace and quiet, etc. – Emma foresees a year of boredom, frustration and domesticity ahead. She will be lost out there in the wilds – isolated and insignificant.

Drabble is great on the nitty-gritty of daily life, capturing just how patronising a man can be to his wife or partner. So much of this dialogue rings true to me – especially the last line, which is a killer.

[David:] ‘You can get another job. Someone like you can get any number of jobs.’

[Emma:] ‘In Hereford?’

‘Well, I’m sure there’s something you could find to do there.’

‘You think so? Perhaps I could apply to be an usherette at your theatre, you mean?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, my love. There must be something you can do.’

‘I’m sure, on the contrary,’ I said, ‘that there would be simply, literally nothing that I could do.’

‘You could look after the children.’ (p. 16)

So, reluctant to split up the family while her husband pursues his ambitions, Emma has little option but to up sticks and move to Hereford for the season, leaving her broadcasting opportunity behind. Naturally, she expresses her frustration over the situation, but it’s of little use – after all, the man’s career must come first.

While David would naturally gravitate towards a modern house for comfort and convenience, Emma shuns anything new, opting instead for an older, characterful property despite its impractical nature. It’s a choice that illustrates their different personalities, partly explaining why they match relatively well as a couple irrespective of their bickering!

With David busy in rehearsals all day, Emma sees very little of him, especially when his work spills into the evenings. Moreover, everyone that Emma meets in Hereford assumes she must be an actress or something to do with the theatre. Otherwise, why else would she be there?

Consequently, she finds herself drawn into a dalliance with the director, Wyndham Farrar, who is well into his forties. In truth, only the ‘dark and wanting part’ of Emma responds to Wyndham’s advances, hijacking the rest of her to submit to its whims. Deep down, she knows the affair is ill-judged, but somehow, she cannot stop herself from succumbing, despite recognising it as a sign of her ‘own inadequacy and inability to grow’.

There would have been no point in saying no, and yet I felt that I had involved myself in disaster by saying yes. It was not merely that our appointment had a distinct flavour of the clandestine, nor that Wyndham Farrar himself seemed to be a dangerous undertaking, though both these factors were involved. It was more that the way I had said yes, the helpless, rash, needing way I had been unable to refuse, laid me open to all sorts of conjectures about myself and my position. (p. 90)

In short, the responsibilities of marriage and motherhood, of constantly caring for two small children, have subsumed Emma’s own personal ambitions. All her social, cerebral and emotional needs have been suppressed – hence Emma’s craving for recognition and self-validation, which Wyndham taps into with his advances, albeit superficially.

I don’t want to reveal too much about how this story plays out, other than to say that Emma comes to a realisation. She is neither the self-pitying type nor the romantic, self-indulgent type who would feel satisfied by an affair with Wyndham. Rather, she is not cut out for it at all.

While there are several novels about the limitations of marriage, motherhood and the desire to feel valued, the sharpness of Drabble’s writing gives The Garrick Year an edge. The novel is laced with wry, pointed humour – partly from Emma’s lively narrative voice, which feels spiky and true.

I stared hard at people to stop them staring at me: this is one of my amusements. (p. 46)

Drabble’s flair for a cutting observation also comes through in her descriptions of the supporting characters – not least with Sophy, the young, talkative actress fresh out of drama school, who catches David’s eye. She is glossy, well-dressed and a little dim – perfect fodder for the local press and their eager photographers.

She was clearly in her element: she was made, one could tell, for that gluttonous negative machine. (p. 47)

The respected actress, Natalie Winter – a woman with no dress sense whatsoever – also falls under Emma’s penetrating gaze.

She was wearing a cocktail dress in emerald green, a colour better left to emeralds, with a black satin evening bag and white satin shoes (p. 46)

Drabble is also terrific on the world of reparatory theatre and the people within it – an environment she knew well through her marriage to the classically trained actor Clive Swift.

I like watching rehearsals: they are far more interesting than performances. One can see in a rehearsal every detail of what has preceded: who loves whom, who is nervous, who is confident, who is vain, who has been bullied by the director, who is admired by the rest of the cast, who is on the verge of tearful disaster. (p. 83)

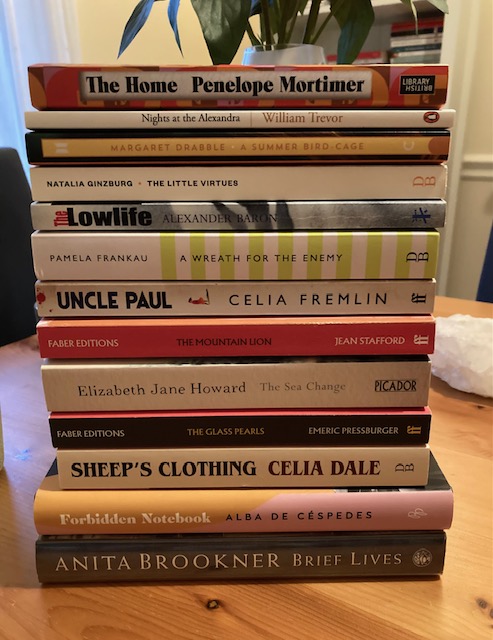

The novel’s 1960s setting – a time of pivotal social change – also makes it feel distinctive. Even though I’ve yet to read The Pumpkin Eater, I couldn’t help but be reminded of Penelope Mortimer’s brilliant, incisive short stories, Saturday Lunch with the Brownings, as I was reading this book.

So, in summary then, The Garrick Year is another excellent novel by Margaret Drabble – a perceptive exploration of the frustrations of putting aside one’s own career and life ambitions for the sake of one’s partner. It’s also very insightful on the minutiae of daily life for a young mother with small children, how you can never take your eyes off a toddler for more than a couple of seconds when out and about. Very highly recommended, especially for readers interested in women’s lives in the mid-20th century.