In 1928, German schoolmaster Hans Herbert Grimm anonymously published his first and only book, the semi-autobiographical anti-war novel, Schlump. Despite its obvious literary merits, Schlump was somewhat overshadowed at the time by the success of another WW1 novel, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (somewhat ironically, the two books were issued within weeks of each other). In the early 1930s, Schlump was burned by the Nazis. In an effort to keep his authorship of the book a secret, Grimm concealed the original manuscript of Schlump in the wall of his house in Germany where it remained until its discovery in 2013. Now, thanks to the efforts of Vintage Books, NYRB Classics and the translator Jamie Bulloch, a whole new generation of readers can experience this rediscovered classic for themselves. Given the book’s history, it seemed a fitting choice for Caroline and Lizzy’s German Lit Month which is running throughout November.

The novel itself focuses on the wartime experiences of Emil Schulz (known to all as ‘Schlump’), a bright and eager young man who volunteers for the German infantry on his seventeenth birthday. In August 1915, Schlump sets off for the barracks in readiness for the adventures ahead. Perhaps like many other young men at that time, he has a rather romanticised vision of life as a soldier, a view which is typified by the following passage.

He could picture himself in a field-grey uniform, the girls eyeing him up and offering him cigarettes. Then he would go to war. He pictured the sun shining, the grey uniforms charging, one man falling the others surging forward further with their cries and cheers, and pair after pair of red trousers vanishing beneath green hedges. In the evenings the soldiers would sit around a campfire and chat about life at home. One would sing a melancholy song. Out in the darkness the double sentries would stand at their posts, leaning on the muzzles of their rifles, dreaming of home and being reunited with loved ones. In the morning they’d break camp and march singing into battle, where some would fall and others be wounded. Eventually the war would be won and they’d return home victorious. Girls would throw flowers from windows and the celebrations would never end. (pp. 6-7)

As luck would have it, Schlump’s first experience of war turns out to be a fairly gentle one. Armed with his school-leaver’s certificate and a grasp of the local language, Schlump is posted to Loffrande in France where he is put in charge of the administration of three villages, a task he soon gets to grips with, overseeing the work of the villagers and intervening in various matters in need of his attention. A good man at heart, Schlump gets on well with the locals, especially the rather high-spirited young girls who see to it that he is not short of female companionship.

Everything is relatively peaceful here in the countryside, so much so that it would be relatively easy for our protagonist to forget his true status as a soldier were it not for the faint rumble of cannons in the background. Sadly though, all good things must come to an end, and after a season in Loffrande, Schlump hears that he is to be sent to the Front. Somewhat understandably, he feels a mixture of anger and disappointment; in some ways, it is almost like leaving home for a second time. As a sergeant from the service corps says before Schlump departs for the battlefield, ‘Only fools end up in the trenches, or those who’ve been in trouble.’

The relative calm of Schlump’s introduction to life as a soldier only serves to accentuate the horrors that follow. Like Remarque, Grimm doesn’t hold back on the true nature of life in the trenches; the physical and mental effects of war are conveyed here in a fair bit of detail. In this scene, Schlump’s regiment is under attack from the British (the Tommies).

One, two! Those were the small shells; now the heavy one would be on its way. Yes, there it was. A terrible explosion, and Schlump was given a sharp jolt by the wall he was leaning against. A loud boom came from the dugout. Schlump teetered forward. The heavy shell had hit the machine-gun nest and the hand grenades had exploded. Two soldiers shot high into the sky; Schlump had a clear view of them, their arms and legs spread-eagled. And around the two bodies innumerable tiny black dots reeled: fragments of stone and dirt. Everything landed on the Tommies’ side. The trench was completely destroyed. There was no trace of the other two machine gunners. Schlump crawled out of the rubble and checked that his legs were still in one piece. (pp.114-115)

Grimm is particularly strong on the gruelling, precarious rhythm of life in the trenches: the constant exhaustion from operating on two hours sleep; the additional discomfort from rampant infestations of lice; the seemingly never-ending periods of standing guard; the perpetual feeling of exposure; the fetching and carrying of food, most of which gets spilled on the battlefield (that’s if it makes it at all – in some instances the carriers will die or suffer severe injuries en route).

Schlump does not escape the war unharmed; there are a couple of occasions when he is hospitalised and sent back to Germany to recuperate, periods which also serve to highlight the debilitating effects of war on those left behind. During a brief visit home, Schlump finds his father a mere shadow of the man he once was, forced to work in a factory as no one is in need of the services of a tailor any more.

In spite of everything the war has to throw at him, Schlump remains, for the most part, optimistic. Only once or twice does his spirit come close to fracturing, most notably when a pregnant girl is killed by a bomb while crossing the marketplace in her village, an act which provokes a sense of outrage and dismay at the cruelty of war. Moreover, Schlump is not blind to the hypocrisy of those in charge of the foot soldiers, the higher-ups who shield themselves from any personal danger or discomfort. The contrast in the following passage is plain to see.

And then that time when they’d been resting, when the first company had returned from the front trenches, those wretched fellows had looked ghastly: emaciated, ashen-faced, grubby chalk worked around the stubble, stooped, utterly worn out, filthy, terribly filthy, lice-ridden and bloody, and only twenty men left of the sixty who’d been positioned on the front line. These men were standing by their quarters when the fat sergeant major came out, who’s spent each one of the twelve nights playing cards and getting drunk. This sergeant major, the mother superior of the company came and ranted at them as if they were common criminals. If that wasn’t contempt, then what was? (pp. 120-121)

The somewhat episodic nature of this novel makes it difficult to capture in a review. In many ways, it reads like a series of vignettes centering on Schlump’s experiences of the war from 1915-18. My Vintage Books edition of Schlump comes with an excellent afterword by the German writer Volker Weidermann – author of Summer Before the Dark, a book set before the start of WW2 – who describes Grimm’s novel as a docu-fable. It’s an apt description, particularly given the nature of the some of the episodes in the book. There is a fable-like quality to several of the tales and stories peppered throughout the narrative. Almost every character Schlump encounters has a story to tell, an anecdote or myth of some sort, a feature which adds to a feeling of the margins being blurred. In certain instances, it is not always easy to distinguish between what is meant to be ‘real’ and what is more likely to be a horrific nightmare or fantasy of some sort.

I’m very glad to have discovered this book via Grant’s excellent review last year. Schlump is a very endearing character, forever the scallywag, the chancer and the dreamer, always looking to sneak away from his place of confinement in search of girls. In spite of the undeniable horrors of war, Grimm brings a great deal of humour to this story, especially the first part of the book when his protagonist is stationed in France. There is a sense of universality about this story, almost as though Schlump could have been any soldier in any regiment in the Great War. It’s one of the things that makes this novel so relevant to readers everywhere, irrespective of their nationality.

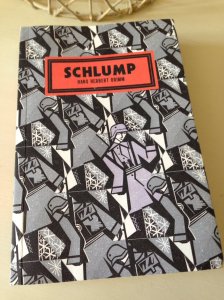

This does sound good – and oh my, what a cover!

The cover’s great, isn’t it? I love the way Schlump stands out from the crowd there!

I have obviously fallen victim to the ‘close to the Remarque novel publication date’ because I’d never heard of this one. Will have to seek it out, sounds quite compelling!

In some ways, I’m not surprised that you hadn’t heard of it before as it was lost for so many years. Vintage published this edition last year, and there’s a new one coming from NYRB later this month (presumably for the stateside market). Hopefully this will give the novel a bit of a boost as it’s definitely worth seeking out!

By the way, the afterword mentions another book that appeared at the same time on a similar subject: War by Ludwig Renn. I’m not sure if you’ve ever heard of it but it’s a new one on me. Isn’t it funny how all three were published at roughly the same time some ten years after the end of the Great War…

Not heard of that one either – but it’s not surprising that they all appeared at roughly the same time. It takes a while to digest such experiences. Books about the Communist era and its aftermath in Romania only started to appear 8-12 years after 1989.

That’s a good point about needing some time to reflect on such a traumatic experience. Looking again at Weidermann’s afterword, he makes the point that the ‘first proper literary engagement with WW1, the questions of everyday life during the war, the heroism and futility,’ only started to emerge in the second half of the 1920s. As you say, maybe it’s not so surprising after all…

The story of how it came to be discovered would be interesting to learn – how did it survive intact, undiscovered for so many decades?

There is a little more about the story behind the book in Weidermann’s afterword, but it doesn’t actually say what prompted the rediscovery in 2013. It’s clear that Grimm had hidden the manuscript in a crack in the living room wall in his house in Altenberg, but I’m not sure it came to light. (At the time he was afraid of being discovered as the author of an anti-war novel and of the imprisonment/persecution that would almost certainly follow. He even joined the Nazi Party so he could live and work in safety even though in reality he valued tolerance and compassion.) Grimm’s story is very sad as he was prevented from teaching after the Second World War. In 1950, he committed suicide following a summons to meet with the authorities of the newly-established GDR. He never told anyone what was discussed at the meeting, but it must have been something devastating – two days later he took his own life.

Oh, how sad.

Great review Jacqui. Sounds like a really powerful read and how astonishing that it was lost for so long. And how good that it’s now available again!

Thanks, Karen. Yes, absolutely – it’s good to see it back in print again.

Very interesting. I’m not familiar with the book but it could be a worthy choice for next year’s Readalong. I can see how All Quiet would have overshadowed everything else.

It sounds not as dark as Remarque’s novel. Maybe it has influences of picaresque novels. I have a feeling there’s a similar older book.

That’s a great thought about possibly including it in next year’s Literature and War programme. I think it would make a great choice and an interesting companion piece to All Quiet – there’s definitely more humour here, especially in the early sections of the story. The picaresque influence is a very astute observation – in fact, Grant likened Schlump to a character from an 18th-century picaresque novel in his review from last year. He’s a wonderful creation!

I was reminded of Grimmelshausen’s Simplicissimus. That would actually be a bit earlier. 17th century but it makes sense.

I’ve never heard of that one – will have to look it up…

Here

Oh my goodness, that sounds like a wild ride. Thanks for the link!

This one is also on my list. It is being reissued in Nov. by NYRB classics in the US.

That’s great! I’ll be interested to see what you make of it. Good timing for the NYRB issue too, especially with GLM running through till the end of November. I hope the new edition will give it a bit of a boost as it deserves to be better known.

Glad you reviewed this one Jacqui. I have a copy of it too and have selected it for this month as well.

Oh, that’s great news. I’m looking forward to seeing your take on it. Really hope you like it. Caroline mentioned the possibility of including it in the programme for the Literature and War Readalong, so I’m sure she’ll be very interested in your views.

Mine’s the NYRB edition too

I’d heard of this novel, but hadn’t registered it had had such a tortuous history. Another tantalizing review, Jacqui — many thanks!

You’re very welcome, John. I’m really glad I read this one, and it made for an interesting comparison with the Remarque. The book’s history is fascinating if somewhat tortuous, especially for Grimm himself. There’s a new edition coming soon from NYRB, so you may well end up hearing a little more about it over the next few months.

Lovely review Jacqui. It’s always interesting, and important I think, to read of war from the point of view of the soldier, and it sounds like Grimm has put into the book his own experience of the war. How many boys went to war as naively as Schlump did? It’s a shame the book remained hidden as long as it did, but nice that it’s come back into print.

Thanks, Belinda. Yes, I agree – I have to give myself a little push every now and again to read about the wars, but I always feel better for doing so. It’s important that we remember these soldiers and learn a little more about their experiences back then – fiction can be a great way of achieving this. I’m delighted to see this back in print – it turned out to be a great discovery for me.

Yes, I agree it is very important to hear the soldiers’ stories. And promote them too, as you’ve done here. Not a book I’d have come across otherwise.

Glad to have introduced you to it. :)

Goodness me this does sound good. I has never heard of it before – and what a fascinating history it has. I loved All Quiet on the Western Front.

It’s well worth considering, especially as you loved All Quiet so much. Isn’t the book’s history fascinating? As BookerTalk was saying earlier, it would make quite a story in its own right.

Oh yes absolutely. A film about it would also be wonderful.

Yes, agreed.There’s more than enough material for a decent film here…

That’s a great cover, I’ll have to see how the NYRB cover compares. The cover art looks like Art Spiegelman’s work.

Have you read ‘The Good Soldier Svejk’? I like the concept of humorous WWI stories.

Isn’t it just! I love the way that one figure stands out from the crowd. Plus it seems to capture something of his character too – Schlump, forever the scallywag and survivor. Here’s a link to the NYRB edition. I think I prefer the Vintage cover, but the NYRB version is interesting as well.

http://www.nyrb.com/products/schlump?variant=19280884359

No. I haven’t read The Good Soldier Svejk, but it’s been on my wishlist for the longest time! Oh dear, I can feel another purchase coming on…

Thanks Jacqui. Yes, I prefer the Vintage one too.

Thanks, Jacqui, for another excellent review. The title rings a faint bell, but I can’t remember where I might have heard about the book. I would love to read it to compare it to Remarque; from your review, I can see how it might not be as bleak as All Quiet. Let’s see if it becomes part of Caroline’s readalong next year. That would be an excellent reason to get the book. (I would have to insist on the Vintage edition… love the cover.)

You’re very welcome. It would be great if Caroline decides to include it in next year’s readalong. I think it would make an interesting choice for the Lit and War series, especially given the timing of publication and the book’s history. As you say, let’s see what happens, but I hope you get a chance to read it at some point. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Isn’t the Vintage cover terrific? Everybody seems to love it!

This history behind this book is so interesting! And, what a great title and cover! I feel like I’m always saying it, but some just really grab your attention.

Yes, quite a story in its own right. I wonder how the manuscript was found in 2013. The afterword gives quite a bit of the background, but I’m still not sure what happened in the run-up to the discovery itself…

The cover is very eye-catching, isn’t it. And I love the way Schlump’s figure stands out from the masses. The fact that he’s facing the opposite way is quite indicative of his character, I think.

Interesting comment about a ‘series of vignettes’. War novels often have a powerful narrative drive, but I’m sure the actual reality of war is closer to this- a series of horrible events, periods of calm and even boredom and unlikely comedy.

Yes, it feels quite realistic in that respect. Grimm’s very good on the monotony of war, the gruelling rhythm of life on the front – there’s a lot of hanging around and killing time. It must have been so hard for them, both mentally and physically…

I am currently reading the NYRB edition. I enjoyed your post a lot. I loved the episode where a village boy gets a chamber pot stuck on his head.

Oh, great. I’m glad you enjoyed my post. Yes, there are some wonderfully comic vignettes, especially in the section where he’s stationed in Loffrande. I loved the bit where a new recruit is charged with the task of accompanying the local women to a neighbouring village for their shopping and they all scatter in an instant! The poor chap is convinced he’ll end up in the doghouse…

Great review, and thanks for the link!

Interesting that so many people hadn’t heard of this as it was fairly mainstream in bookshops when it came out and, as someone said, it has a very eye-catching cover! Perhaps the rather unrevealing title left it unexplored. (It certainly didn’t seem to get much press coverage).

It does seem to be in the tradition of war novels such as The Good Soldier Svejk and Catch 22, but as I haven’t read either, i can’t say for sure!

Thanks for the heads up on this novel, Grant. I definitely owe you one. That is interesting as I only recall seeing it in Foyles down here – to their credit, it was on prominent display in the new fiction section. Maybe your local bookshops are a little more progressive than some of their London counterparts when it comes to stocking and displaying literature in translation. Or then again, maybe I just failed to spot it!

You’re the second person to mention The Good Soldier Svejk, a book that has been on my ‘one day’ list for such a long time. I must get around to it at some point…

Pingback: A-Z Index of Book Reviews (listed by author) | JacquiWine's Journal

Pingback: My Reading List for The Classics Club | JacquiWine's Journal

Pingback: Schlump: Hans Herbert Grimm | His Futile Preoccupations .....

Pingback: German Literature Month VI: (Belated) Author Index | Lizzy's Literary Life