I don’t usually mark my blog’s birthdays, but as JacquiWine’s Journal is 10 years old today, I couldn’t resist this post as a celebration of sorts! It seems such a long time since I first dipped my toe in the blogging world with some reviews of books longlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2014. I was part of a Shadow Panel back then, and initially, the other shadowers kindly posted my reviews on their blogs as I didn’t have one of my own – not until I set up the Journal in May 2014, and the rest as they say is history.

Much has changed since I started blogging, but the bookish community on various sites and social media platforms continues to be a joy. I’ve had so many lovely conversations with readers over the years, so thank you for reading, engaging with and commenting on my reviews – I really do appreciate it.

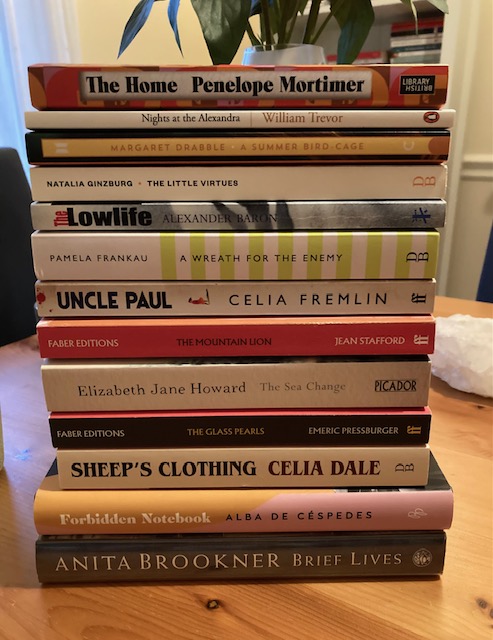

To mark this milestone, I’ve selected a favourite book reviewed during each year of my blog, up to and including 2023. (My favourite reads of 2024 will have to wait till later this year!) Happy reading – as ever, you can read the full reviews by clicking on the appropriate links.

Cassandra at the Wedding by Dorothy Baker (reviewed in 2014)

Cassandra, a graduate student at Berkeley, drives home to her family’s ranch for the wedding of her identical twin sister, Judith, where she seems all set to derail the proceedings. This is a brilliant novel featuring one of my favourite women in literature. Cassandra is intelligent, precise and at times witty, charming and loving. But she can also be manipulative, reckless, domineering, self-absorbed and cruel. She’s a mass of contradictions and behaves abominably at times, and yet it’s very hard not to feel for her. If you like complex characters with plenty of light and shade, this is the novel for you!

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor (reviewed in 2015)

Taylor’s 1971 novel follows a recently widowed elderly lady, Mrs Palfrey, as she moves into the Claremont Hotel, joining a group of residents in similar positions – each one is likely to remain there until a move to a nursing home or hospital can no longer be avoided. This beautiful, bittersweet, thought-provoking novel prompts readers to consider the emotional and physical challenges of old age: the need to participate in life, the importance of small acts of kindness and the desire to feel valued, to name just a few. Taylor’s observations of social situations are spot-on – there are some very funny moments here alongside the undoubted poignancy. Probably my favourite book by Elizabeth Taylor in a remarkably strong field!

In a Lonely Place by Dorothy B. Hughes (reviewed in 2016)

A superb noir which excels in the creation of atmosphere and mood. As a reader, you really feel as though you are walking the Los Angeles streets at night, moving through the fog with only the dim and distant city lights to guide you. Hughes’ focus is on the mindset of her central character, the washed-up ex-pilot Dix Steele, a deeply damaged and vulnerable man who finds himself tormented by events from his past. The storyline is too complex to summarise here, but Hughes maintains the suspense throughout. (This was a big hit with my book group, and we went on to read The Expendable Man, too!)

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (reviewed in 2017)

A beautiful and compelling portrayal of forbidden love, characterised by Wharton’s trademark ability to expose the underhand workings of a repressive world. Set within the upper echelons of New York society in the 1870s, the novel exposes a culture that seems so refined on the surface, and yet, once the protective veneer of respectability is stripped away, the reality is brutal, intolerant and hypocritical. There is a real sense of depth and subtlety in the characterisation here. A novel to read and revisit at different stages in life.

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne by Brian Moore (reviewed in 2018)

This achingly sad novel is a tragic tale of grief, delusion and eternal loneliness set amidst the shabby surroundings of a tawdry boarding house in 1950s Belfast. Moore’s focus is Judith Hearne, a plain, unmarried woman in her early forties who finds herself shuttling from one dismal bedsit to another in an effort to find a suitable place to live. When Judith’s dreams of a hopeful future start to unravel, the true nature of her troubled inner life is revealed, characterised as it is by a shameful secret. The humiliation that follows is swift, unambiguous and utterly devastating, but to say any more would spoil the story. An outstanding, beautifully written novel – a heartbreaking paean to a life without love.

A Dance to the Music of Time by Anthony Powell (reviewed in 2019)

I’m cheating a little by including this twelve-novel sequence exploring the political and cultural milieu of the English upper classes, but it’s too good to leave out. Impossible to summarise in just a few sentences, Powell’s masterpiece features one of literature’s finest creations, the odious Kenneth Widmerpool. It’s fascinating to follow Widmerpool, Jenkins and many other individuals over several years in the early-mid 20th century, observing their development as they flit in and out of one another’s lives. The author’s ability to convey a clear picture of a character – their appearance, their disposition, even their way of moving around a room – is second to none. Quite simply one of the highlights of my reading life!

The Children of Dynmouth by William Trevor (reviewed in 2020)

Probably my favourite William Trevor to date, The Children of Dynmouth tells the story of a malevolent teenager and the havoc he wreaks on the residents of a sleepy seaside town in the mid-1970s. It’s an excellent book, veering between the darkly comic, the deeply tragic and the downright unnerving. What Trevor does so well here is to expose the darkness and sadness that lurks beneath the veneer of respectable society. The rhythms and preoccupations of small-town life are beautifully captured too, from the desolate views of the windswept promenade, to the sleepy matinees at the down-at-heel cinema, to the much-anticipated return of the travelling fair for the summer season. One for Muriel Spark fans, particularly those with a fondness for The Ballad of Peckham Rye.

The Fortnight in September by R. C. Sherriff (reviewed in 2021)

During a trip to Bognor in the early 1930s, R. C. Sherriff was inspired to create a story centred on a fictional family by imagining their lives and, most importantly, their annual September holiday at the seaside resort. While this premise seems simple on the surface, the novel’s apparent simplicity is a key part of its magical charm. Here we have a story of small pleasures and triumphs, quiet hopes and ambitions, secret worries and fears – the illuminating moments in day-to-day life. By focusing on the minutiae of the everyday, Sheriff has crafted something remarkable – a novel that feels humane, compassionate and deeply affecting, where the reader can fully invest in the characters’ inner lives. This is a gem of a book, as charming and unassuming as one could hope for, a throwback perhaps to simpler, more modest times.

Quartet in Autumn by Barbara Pym (reviewed in 2022)

First published in 1977, at the height of Pym’s well-documented renaissance, Quartet in Autumn is a quietly poignant novel of loneliness, ageing and the passing of time – how sometimes we can feel left behind as the world changes around us. Now that I’ve read it twice, I think it might be my favourite Pym! The story follows four work colleagues in their sixties as they deal with retirement from their roles as clerical workers in a London office. While that might not sound terribly exciting as a premise, Pym brings some lovely touches of gentle humour to this bittersweet gem, showing us that life can still offer new possibilities in the autumn of our years.

Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes, tr. Ann Goldstein (reviewed in 2023)

A remarkable rediscovered gem of Italian literature, I adored this candid, exquisitely-written confessional from an evocative feminist voice. The novel is narrated by forty-three-year-old Valeria, who documents her inner thoughts in a secret notebook with great candour and clarity, laying bare her world with all its demands and preoccupations. For Valeria, the act of writing becomes a disclosure, an outlet for her frustrations with the family – her husband Michele, a somewhat remote but dedicated man, largely wrapped up in his own interests, which Valeria doesn’t share, and their two grown-up children who live at home. As the diary entries build up, we see how Valeria has been defined by the familial roles assigned to her; nevertheless, the very act of keeping the notebook leads to a gradual reawakening of her desires as she finds her voice, challenging the founding principles of her life with Michele.

If you’ve read any of these books, do let me know your thoughts!