This excellent, beautifully observed novel about identity, friendship and private vs public selves is my first experience of Deirdre Madden’s work; but on the strength of its quiet, unshowy prose and deep insights into character, I will certainly be seeking out more.

Madden’s unnamed narrator – a successful playwright born in Northern Ireland but now living in London – is staying at the Dublin home of her close friend, Molly Fox, while Molly is in New York. The two women have been good friends for around twenty years, ever since Molly – a brilliant actress with a remarkable, distinctive voice – starred in the narrator’s first play, which propelled them both to fame.

As the narrator struggles to crystallise the vision for her new play, she reflects on her life and the relationships she has developed with Molly and others over the years – most notably, her old college friend, Andrew, now a successful art historian and TV presenter comfortable in his own skin; her eldest brother, Tom, a gentle Catholic priest who shares his sister’s interest in the arts; and Molly’s troubled brother, Fergus, who has long suffered intense periods of depression and alcoholism. Many of these memories are triggered by the myriad of possessions in Molly’s modest terraced house, tastefully furnished with interesting pieces acquired over the years. Tasteful that is apart from the absurd fibreglass cow installed in the back garden – a piece so out of kilter with the rest of Molly’s furnishings that the narrator begins to wonder if she knows her friend at all.

I realise that a certain school of thought says that who we are is something we construct for ourselves. We build our self out of what we think we remember, what we believe to be true about our life; and the possessions we gather around us are supposedly a part of this, that we are, to some extent, what we own. (pp. 37–38)

While the narrator has long resisted this idea of the self, partly due to her Catholic upbringing, the realisations that surface during the day challenge her previous beliefs, particularly around Molly – a woman who appears mousy and introverted in polite company but utterly compelling on stage. From her first visit to the theatre as a teenager, Molly understood that the key to being a great actor was to become the character – to inhabit them fully, rather than imitating them. A technique that requires the actor to distance themselves from their own personality and sense of self.

Central to the novel are questions about our private versus public selves. How well do we really know someone, even when we consider them to be a close friend? Who is Molly Fox when she is alone and unobserved, and how does this differ from the person others see when she is elsewhere, e.g. rehearsing in the theatre, meeting fans or socialising with friends? Through the novel’s elegant framework – which unfolds over one day, Molly’s birthday – Madden explores the often-contradictory personalities we adopt in public and private settings.

Madden is excellent on the limits of friendship, the rules of the game, the areas we keep protected and the things we reveal. As the narrator muses over her relationship with Molly, she comes to realise that friendship is not necessarily a clear insight into another person’s psyche but a more clouded vision through which only certain aspects of their world can be gleaned.

The closer you get to Molly, the more she seems to recede. Sometimes she seems to me like a figure in a painting, the true likeness of a woman, but as you approach the canvas the image breaks up, becomes fragmented into the colours, the brushstrokes and the daubs of paint from which the thing itself is constructed. Only by withdrawing can the illusion be effected again. Molly wants to remain remote. (p. 126)

Molly has an unnerving habit of dropping earth-shattering nuggets of information into general conversation as casual, throwaway remarks. Moreover, these bombshells – often covering her earlier life – are delivered when any follow-up discussion or questioning is nigh-on impossible to conduct, leaving the listener reeling as a result. In a fascinating scene, Molly reveals a pivotal event from her 7th birthday, illuminating her fractured upbringing, the intense disdain she holds for her mother, and her fierce protectiveness towards Fergus.

While the narrator’s college friend, Andrew, has also distanced himself from his family, there is no hint of artifice about his personality now he has found his true self. Rather, it is the scruffy, disgruntled student the narrator recalls from her Trinity College days who seems unreal, not the successful TV presenter Andrew is today. If anything, his transformation feels entirely natural and unforced.

There was nothing fake about him, nothing false. It was instead as if he was at last becoming himself, becoming the kind of person he needed to be, the person he really was. It was the tense, prickly man I’d known at college who had been the fake. (p. 68)

The old Andrew was angry with his parents for favouring his brother, Billy, a loyalist paramilitary who was abducted and murdered in Belfast during a politically-motivated feud. In short, their mother never forgave Andrew for being the one left alive when Billy was killed, despite Andrew’s lack of involvement in The Troubles. Only years later, on becoming a father himself, could Andrew appreciate the depth of his parents’ grief over the loss of a much-loved son.

Interestingly, the narrator is also something of a misfit in her own family, although unlike the others, her familial relationships are warm and loving. She is closest to her brother, Tom, the Catholic priest, whom Molly also turns to for guidance – a private friendship which doesn’t include the narrator.

Perhaps most insightful of all is an unexpected encounter between the narrator and Molly’s brother, Fergus, who turns up unexpectedly at the house. As they sit in the garden and talk, the narrator discovers a whole new side to Fergus – a gentle, compassionate, witty and intelligent man, far from the helpless failure she had taken him for before.

Molly. I thought she had won through in life, whilst Fergus was defeated, broken. Now it seemed to me that things were perhaps quite the opposite, and her brother’s woes notwithstanding, Molly was the one who really hadn’t come to terms with the past, who was still bitter about it in a way that was corrosive and did more harm to her than to anyone else. (p.156)

Alongside identity, friendship, family and our private vs public selves, the novel also touches on a number of other topics, including the religious and political divisions within Northern Ireland, familial ties vs personal independence and walking away vs living a lie. Memorialisation is another significant theme. How, for instance, do we remember those who have died or moved on? What is the purpose of memorials, and who are they for – the living or the dead? It’s a topic of great relevance to Andrew, who now sees his brother’s signet ring as a treasured object of remembrance, not the gaudy, embarrassing object it once was.

In summary, this is a marvellous novel – the kind of book where nothing seems to happen, and yet everything is there, just waiting to be uncovered as the layers are peeled away. I’ll finish with a final quote about the tenuous nature of friendship. Here. the narrator reflects on a chance encounter with another old college friend, Marian, whom she hasn’t seen for several years.

Meeting her had been a dispiriting experience, as it so often can be when one meets old friends. The initial delight, the sense of connection, and then the distancing, the unravelling of that connection as information is exchanged and it becomes clear why one hasn’t stayed in touch. Defensiveness sets in, and it all ends in melancholy when one is alone again. (p. 106)

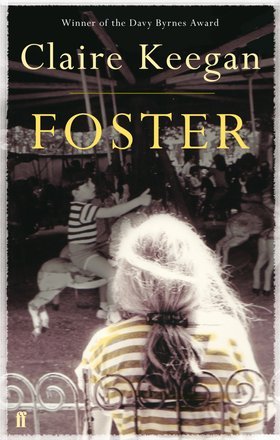

(Molly Fox’s Birthday is published by Faber and Faber; personal copy. This is my first review for Cathy’s Reading Ireland project, which runs throughout March.)