As many of you will know, August is #WITMonth, an annual celebration of books by women writers, initially written in languages other than English and then translated for English-speaking readers to enjoy. It’s an annual event hosted by Meytal at Biblibio, aiming to raise the profile of translated literature by women writers across the globe.

For the last 18 months or so, I’ve been trying to make #WIT a more regular thing by reading and reviewing at least one book by a woman in translation each month (rather than just thinking about them for August). So, if you’re still looking for ideas on what to read for this year’s WIT Month and beyond, here’s a round-up of my recent faves.

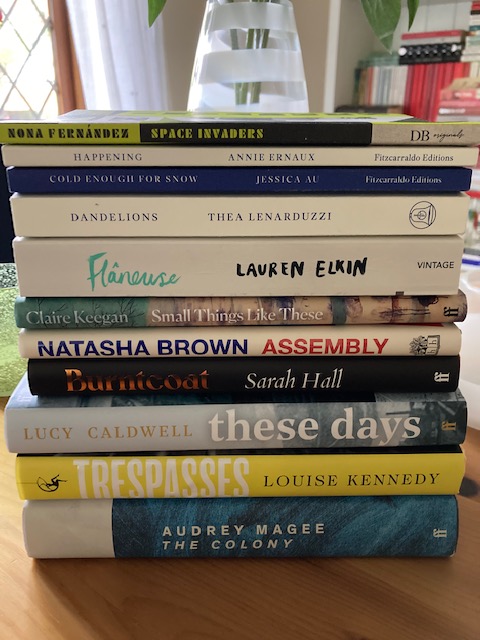

Space Invaders by Nona Fernández (tr. Natasha Wimmer)

First published in Chile in 2013, this memorable, shapeshifting novella paints a haunting portrait of a generation of children exposed to the horrors of Pinochet’s dictatorship in the 1980s – a time of deep oppression and unease. The book focuses on a close-knit group of young adults who were at school together during the ‘80s and are now haunted by a jumble of disturbing dreams interspersed with shards of unsettling memories – suppressed during childhood but crying out to be dealt with now. Collectively, these striking fragments form a kind of literary collage, a powerful collective memory of the group’s absent classmate, Estrella, whose father was a leading figure in the State Police. Fernandez adopts a fascinating combination of form and structure for her book, using the Space Invaders game as both a framework and a metaphor for conveying the story. A stunning achievement by a talented writer – and her recent non-fiction book, Voyager, is just as good!

The Pachinko Parlour by Elisa Shua Dusapin (tr. Aneesa Abbas Higgins)

A couple of years ago, I read and loved Winter in Sokcho, a beautiful, dreamlike novella that touched on themes of detachment, fleeting connections and the pressure to conform to societal norms. Now Elisa Shua Dusapin is back with her second book, The Pachinko Parlour, another wonderfully enigmatic novella that shares many qualities with its predecessor. As in her previous work, Dusapin draws on her French-Korean heritage for Pachinko, crafting an elegantly expressed story of family, displacement, fractured identity and the search for belonging. Here we see people caught in the hinterland between different countries, complete with their respective cultures and preferred languages. It’s a novel that exists in the liminal spaces between states, the borders or crossover points from one community to the next and from one family unit to another. A wonderfully layered exploration of displacement, belonging and unspoken tragedies from times past.

The Trouble with Happiness by Tove Ditlevsen (tr. Michael Favala Goldman)

These short stories – many of which are superb – explore the suffocating nature of family life predominantly from the female perspective, the overwhelming sense of loneliness and anxiety that many women (and children) feel due to various constraints. Here we see petty jealousies, unfulfilled desires, deliberate cruelties and the sudden realisation of deceit – all brilliantly conveyed with insight and sensitivity. What Ditlevsen does so well in this collection is to convey the sadness and pain many women and children experience at the hands of their families. Her characters have rich inner lives, irrespective of the restrictions placed on them by society and those closer to home. The writing is superb throughout, demonstrating the author’s skills with language and a flair for striking one-liners with a melancholy note.

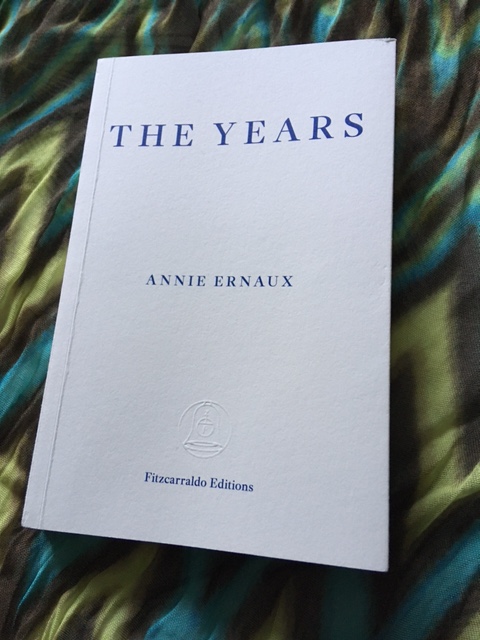

Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux (tr. Tanya Leslie)

I’ve read a few of Ernaux’s books over the past 18 months, and Simple Passion is one of the best. In just under forty pages, Ernaux reflects on the emotional impact of her two-year affair with an attractive married man in the late 1980s. Rewinding to that time, we find Ernaux approaching fifty, while her lover — a smart, well-dressed Eastern European with a resemblance to Alain Delon — is thirteen years younger. Ernaux’s passion for this man is all-consuming, to the extent that virtually everything she does revolves around their liaison. As ever with this writer, the approach is deeply introspective, moving seamlessly between recollections of the ‘feel’ of the affair and the process of writing about it. The writing is clear, precise and emotionally truthful throughout. Moreover, there is a beauty to Ernaux’s prose – a degree of elegance that belies its simplicity. This is an exquisite book by a very accomplished writer – so honest, insightful and true. Best read in one sitting to maximise the impact.

Elena Knows by Claudia Piñeiro (tr. Frances Riddle)

Shortlisted for last year’s International Booker Prize, Elena Knows is an excellent example of how the investigation into a potential crime can be used as a vehicle in fiction to explore pressing societal issues. In short, the book is a powerful exploration of various aspects of control over women’s bodies. More specifically, the extent to which women are in control (or not) of their own bodies in a predominantly Catholic society; how religious dogma and doctrines exert pressure on women to relinquish that control to others; and what happens when the body fails us due to illness and/or disability. While that description might make it sound rather heavy, Piñeiro’s novel is anything but; it’s a hugely compelling read, full of depth and complexity. When Elena’s daughter, Rita, is found dead, the official investigations deliver a verdict of suicide, and the case is promptly closed by the police. Elena, however, refuses to believe the authorities’ ruling based on her knowledge of Rita’s beliefs, so she embarks on an investigation of her own with shocking results…

Iza’s Ballad by Magda Szabó (tr. George Szirtes)

Set in Hungary in the early 1960s, Iza’s Ballad is a heartbreaking portrayal of the emotional gulf between a mother and her daughter, two women with radically different outlooks on life. When her father dies, Iza decides to bring her elderly mother, Ettie, to live with her in Budapest. While Ettie is grateful to her daughter for this gesture, she struggles to adapt to modern life in the city, especially without her familiar possessions and the memories they represent. This is a novel of many contrasts; the chasm between the different generations; the traditional vs the new; the rural vs the urban; and the generous vs the self-centred. Szabó digs deep into the damage we inflict on those closest to us – often unintentionally but inhumanely nonetheless.

The Little Virtues by Natalia Ginzburg (tr. Dick Davis)

A luminous collection of essays by one of my favourite women in translation – erudite, perceptive and full of the wisdom of life. In her characteristically lucid prose, Ginzburg writes of families and friendships, of virtues and parenthood, and of writing and relationships. For instance, in ‘My Vocation’ (1949), Ginzburg traces her approach to writing over the arc of her creative life, from composing juvenile poems and stories in childhood to her maturity as a writer of the female experience in adulthood. It’s a fascinating piece detailing how her relationship with writing has changed through adolescence, marriage and motherhood. There is so much wisdom and intelligence to be found in these essays. Or, if you prefer fiction, Ginzburg’s All Our Yesterdays and The Dry Heart are well worth considering.

Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Cespedes (tr. Ann Goldstein)

This is a remarkable rediscovered gem of Italian literature – a candid, exquisitely-written confessional from an evocative feminist voice. The novel is narrated by forty-three-year-old Valeria Cossati, who documents her inner thoughts in a secret notebook with great candour and clarity, laying bare her world with all its demands and preoccupations. For Valeria, the act of writing becomes a confessional of sorts, an outlet for her frustrations with the family – her husband Michele, a somewhat remote but dedicated man, largely wrapped up in his own interests, which Valeria doesn’t share, and their two grown-up children who live at home. As the diary entries build up, we see how Valeria has been defined by the familial roles assigned to her; nevertheless, the very act of keeping the notebook leads to a gradual reawakening of her desires as she finds her voice, challenging the founding principles of her life with Michele.

I adored this illuminating exploration of a woman’s right to her own existence in the face of competing demands. (Fans of this book might also appreciate Anna Maria Ortese’s stories and reportage, Evening Descends Upon the Hills, another superb #WITMonth read from Pushkin Press.)

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck (tr. Michael Hofmann)

East Germany in the late 1980s is the setting for Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel, Kairos, in which the rhythms of a corrosive love affair are reflected in the fate of this country in the years leading up to its demise. The relationship in question begins in the summer of 1986 when nineteen-year-old Katharina meets Hans – a married writer, thirty-four years her senior – by chance on a bus. The attraction is instant, and an intense affair swiftly follows, cemented by a shared love of classical music. Erpenbeck is excellent on the messiness of an illicit liaison; the secrets and lies; the uncertainties surrounding the future; how quickly the present slips into the past with each passing moment. As we follow the couple over the next three years, we see how their story is entwined with that of East Germany in the run-up to the fall of the Wall, complete with all the crumbled hopes and dashed dreams the failure of this idealistic state represents. In many ways, this is a novel of beginnings and endings, a concept equally applicable to intimate relationships and countries/states. In short, Erpenbeck has given us a highly compelling combination of the personal and political here, a must-read for anyone interested in this era of German history and culture.

Cold Nights of Childhood by Tezer Özlü (tr. Maureen Freely)

First published in Turkish in 1980 and now available in English for the first time, this highly evocative novella comprises a series of impressionistic fragments of a young woman’s life – a life that bears many similarities to Tezer Özlü’s own. By sifting and rearranging these fragments in the mind, we gain early glimpses of the narrator in her homeland. A childhood spent in a restrictive, patriarchal family presided over by a tyrannical father; her mother trapped in a loveless marriage lacking any sense of warmth and affection. Özlü is particularly strong on how fear, loneliness and depression can grind a person down, reducing them to nothing. In adulthood, there are unfulfilling, loveless marriages, periods of despair, and horrific incarcerations in psychiatric hospitals where the narrator is mentally and physically abused. Nevertheless, the novella ends on a wonderfully optimistic note as this young woman emerges from the darkness, ready to embrace life and a renewed sense of wonder in the everyday. This is a remarkably powerful portrait of a young Turkish woman trying to carve out a space for herself in an oppressive but rapidly transforming society. Özlü’s ability to immerse the reader in the protagonist’s fractured inner world, and her vivid depictions of female desire in the face of a brutal, patriarchal society, are truly impressive.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Let me know what you think of these books if you’ve read some of them already or if you’re considering reading any in the future. Maybe you have a favourite book by a woman in translation? If so, please feel free to mention it below.

You can also find some of my other favourites in my WIT Month recommendations posts from July 2020, 2021 and 2022, including books by Olga Tokarczuk, Françoise Sagan, Irmgard Keun, Ana Maria Matute and many more. Hopefully, there’s something for everyone here!