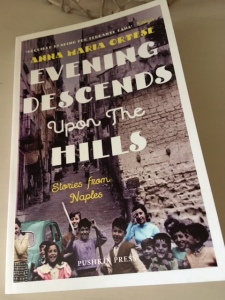

First published in Italian in 1953, Evening Descends Upon the Hills is a brilliant collection of short stories and reportage by the critically acclaimed writer Anna Maria Ortese. As a whole, the collection conveys a vivid portrait of post-war Naples in all its vitality, devastation and squalor – a place that remains resilient despite being torn apart by war. Sharp contrasts are everywhere Ortese’s writing, juxtaposing the city’s ugliness with its beauty, the desperation of extreme poverty with the indifference of the bourgeoisie, the reality of the situation with the subjectivity of our imagination. It’s a powerful and evocative read, enhanced considerably by Ortese’s wonderfully expressive style.

Evening begins with three fictional pieces – the first of which is A Pair of Eyeglasses, an excellent story in which a young girl, Eugenia, is eagerly anticipating her first pair of glasses. Eugenia lives with her parents, spinster aunt and two younger siblings in an impoverished neighbourhood of Naples. Partly in return for their basement-level accommodation, Eugenia’s parents are at the beck and call of the Marchesa, the rather demanding and thoughtless owner of the dwelling, who thinks nothing of doling out casual put-downs at various opportunities.

Ortese skilfully captures the inherent spirit of the neighbourhood, complete with a multitude of vivid sights and animated sounds.

When the cart was behind her, Eugenia, raising her protruding eyes, basked in that warm blue glow that was the sky, and heard the great hubbub all around her, without, however, seeing it clearly. Carts, one behind the other, big trucks with Americans dressed in yellow hanging out the windows, bicycles that seemed to be tumbling over. High up, all the balconies were cluttered with flower crates, and over the railings, like flags or saddle blankets, hung yellow and red quilts, ragged blue children’s clothes, sheets, pillows, and mattresses exposed to the air, while at the end of the alley ropes uncoiled, lowering baskets to pick up the pick up the vegetables or fish offered by peddlers. (p. 22)

Nevertheless, it’s an environment that Eugenia is unable to see clearly, particularly as she is virtually blind. Only with the aid of glasses is the true horror of the environment revealed – an experience Eugenia finds utterly overwhelming, shattering her previous perceptions of life in the bustling courtyard.

…the cabbage leaves, the scraps of paper, the garbage and, in the middle of the courtyard, that group of ragged, deformed souls, faces pocked by poverty and resignation, who looked at her lovingly. They began to writhe, to become mixed up, to grow larger. They all came toward her, in the two bewitched circles of the eyeglasses. (p. 33)

The contrast here is particularly striking, pitting Eugenia’s blurred, almost rose-tinted impressions of her surroundings against the brutal reality of the situation. It’s a memorable story, effectively setting the tone for the collection as a whole.

In Family Interior – probably my favourite of the three stories – we meet Anastasia Finizio, a successful shop owner, who has worked tirelessly to support her mother, spinster aunt and younger siblings for several years. At thirty-nine, Anastasia is vaguely aware that her life is slipping by – a realisation brought into sharp relief when she hears news of the return of Antonio, a man from her youth. This development rekindles dormant feelings within Anastasia, prompting her to dream of the kind of life she might have had – and may still to be to have? – with Antonio.

What Ortese does so well here is to convey the power dynamics within the family, particularly in relation to Anastasia’s mother who sees the danger in any disruption to the present equilibrium.

It seemed to Signora Finizio, sometimes that Anastasia wasted time in futile things, but she didn’t dare to protest openly, for it appeared to her that the sort of sleep in which her daughter was sunk, and which allowed them all to live and expand peacefully, might at any moment, for a trifle, break. She had no liking for Anastasia (her beloved was Anna), but she valued her energy and, with It, her docility, that practical spirit joined to such resigned coldness. (p. 48)

In truth, Signora Finizio is a selfish woman, one who takes a perverse satisfaction in hurting Anastasia – effectively humiliating her to keep everything in check. It’s an excellent story, subtle and nuanced in its exploration of Anastasia’s position, highlighting the tension between familial responsibility and personal freedom.

After The Gold of Forcella – a vividly-realised story of a pawnshop in the heart of Naples – the focus shifts to non-fiction pieces, essentially conveyed in a reportage style. The Involuntary City is the most powerful essay in this section – a candid account of Ortese’s visits to Granili III and IV, a sprawling shelter for those made homeless by the devastation of war. Initially intended to be a temporary solution for the displaced and dispossessed, The Granili is ‘home’ to some 3,000 individuals (approximately 570 families), with an average of three families per individual room. The conditions are horrific – damp, cramped and filthy – particularly on the lower floors of the building where the most impoverished residents are housed.

In a few homes someone was cooking: smoke, which had the density of a blue body, escaped from some doors, yellow flames could be glimpsed inside, the black faces of people squatting, holding a bowl on their knees. In other rooms, instead, everything was motionless, as if life had become petrified; men still in bed turned under grey blankets, women were absorbed in combing their hair, in the enchanted slow motion of those who do not know what will be, afterward, the other occupation of their day. The entire ground floor, and the first floor to which we were ascending, were in these conditions of depressed inertia. (pp. 86-87)

There is a sense of desperation about the existence in these squalid, smoke-ridden conditions, almost as if the building’s lower echelons are representative of a race’s demise following the destructive impact of war.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a form of class structure has developed within the Granili, separating the displaced into different social strata, largely according to status. Some of those on the higher floors have jobs – consequently their days are structured, and this sense of order tends to be reflected in the immediate surroundings. In short, these individuals have adapted to reduced circumstances without giving up their sense of decorum. Nevertheless, there is a widespread understanding of the precarious nature of this situation. On occasions a random stroke of bad luck, such as an illness or the loss of a job, will force someone on the third floor to give up their lodgings and descend to a lower one, usually to move in with another family member. For the most part, these people are destined to remain in their relegated positions, despite harbouring hopes of regaining their previous status.

In the final section of the book, Ortese recounts a series of journeys to visit former colleagues from Sud, the avant-garde cultural magazine where she worked in the late ‘40s. There is a melancholy, elegiac tone running through these pieces, a sense of alienation from those who have become indifferent or embittered.

In summary, Evening Descends Upon the Hills is a fascinating collection that blurs the margins between fiction and reportage to paint a striking vision of post-war Naples, vividly capturing the city’s resilience in the face of poverty, suffering and corruption. The attention to detail is meticulous – as is the level of emotional insight, particularly about women’s lives and family dynamics.

The collection comes with an excellent introduction by the translators which outlines the reactions to Ortese’s candid (and sometimes brutal) vision of Naples following the book’s initial publication – the author was subsequently banned from the city for several years. Also included is the preface from the 1994 reissue, in which Ortese reflects on how her disoriented state of mind may have influenced her picture of post-war Naples, as captured in the original book.

In short, this is very highly recommended indeed – particularly for fans of Elena Ferrante, who has cited Ortese as a key influence on her work. My thanks to Pushkin Press and the Independent Alliance for kindly providing a review copy.